The Supreme Court is set to tackle in a virtual special session on April 17 the urgent petition filed by a Filipino lawyer that seeks to compel President Rodrigo Duterte to disclose to the public all of his medical records since he took office in 2016.

In a 42-page petition, lawyer Dino de Leon, citing the constitutional provision requiring the public disclosure of the president’s state of health in case of “serious illness,” said the matter has become even more urgent given the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic:

“When everyone’s safety is in peril, the Filipino People should at least have the information on the health of the main decision maker…to ensure that [he] is physically and mentally fit to be at the helm of the government…”

Source: Dino de Leon Facebook account, Petition for Mandamus – De Leon vs. Duterte, April 13, 2020

De Leon proceeded to enumerate a number of diseases Duterte had publicly admitted to have. He also cited several instances when the president missed official functions due to health reasons.

Malacanang brushed off the petition, with newly reinstated Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque, who is also a lawyer, “predicting” that it will be dismissed by the 15-member high court, which currently has 12 Duterte appointees, including Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta.

Does the public have the right to know exactly what ails the president? And why does it matter?

Here are five things you need to know:

1. What does the Constitution say about disclosure of the president’s state of health?

Sec. 12, Art. VII of the 1987 Constitution requires that the public be informed of the president’s state of health in case of serious illness.

It also specifically states that, in such cases, the military chief and members of the Cabinet in charge of national security and foreign relations “shall not be denied access” to the president.

During the 1986 Constitutional Commission (ConCom) debates, the late Sen. Blas Ople, who proposed this provision, said this is important because:

“…the safeguarding of our national survival and security can be irretrievably impaired if the access of those in charge of national security and foreign relations is cut off.”

Source: Record of the Constitutional Commission Volume II, p. 459

This was not included in the 1935 and 1973 Constitution.

When the provision was proposed, Ople said, historically, there had been “many recorded instances” where the president, or leader, concealed his state of health from the public, and that such illness can occur during an “awkward moment” where national survival “hangs in the balance.” Hence, at least, the public should be informed.

2. What counts as a ‘serious illness’?

The Constitution itself does not explicitly define what is considered a “serious illness,” but Fr. Joaquin Bernas, a member of the 1986 ConCom and dean emeritus of the Ateneo Law School, said the provision:

“…envisions not just illness which incapacitates but also a serious illness which can be a matter of national concern.”

Source: Bernas, J.G. (2011), The 1987 Philippine Constitution: A Comprehensive Reader

During the interpellation period on the provision in the 1986 ConCom, Ople said it covers medical conditions that “[does] not really [incapacitate] but seriously inconvenience” the president in the conduct of his urgent duties, such as an advanced state of kidney disease that requires treatment by dialysis, among “infinite” examples.

Following the ratification of the 1987 Charter, Duterte’s predecessors adhered to the constitutional provision during their incumbency and even after their respective terms had ended.

In former President Fidel V. Ramos’ case, he issued a medical bulletin on Dec. 23, 1996 before undergoing an operation to remove a “significant carotid (a major artery) block” due to high cholesterol, according to several news reports.

Former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo also issued updates on her health condition, particularly when she was hospitalized in June 2006 for acute diarrhea, and again in June 2009 when the Palace admitted she underwent biopsy tests after lumps were found on her breast and groin.

Post-term, in mid-2011, Arroyo — then entangled in corruption charges — through her doctors, updated the public constantly on her three spine surgeries, as reported by several news outlets.

The late former President Corazon Aquino, through her family, also issued regular updates on her health condition post-term in early 2008, when it was announced that she had colon cancer, until her demise in August 2009.

Former President Joseph “Erap” Estrada’s family and doctors also issued updates on the status of his health after he underwent knee surgery in 2005, and again in 2009 when he was hospitalized after having difficulty breathing.

3. How has Malacanang dealt with Duterte’s health woes so far?

Malacanang has consistently downplayed concerns on the state of Duterte’s health, which has been the subject of rumors and speculation, including death hoaxes, even before he assumed office in 2016. (See DUTERTE’S HEALTH SAGA: A TIMELINE)

Last January, Duterte skipped two rescheduled events — visits to earthquake victims in Davao del Sur — due to health reasons. Chief Presidential Legal Counsel Salvador Panelo, then Duterte’s spokesperson, said the president then just needed to catch up on sleep.

Duterte, the country’s oldest president at 75 years old, has publicly admitted to a number of diseases and medical conditions in previous speeches and interviews, such as:

- Myasthenia Gravis, a “chronic autoimmune, neuromuscular disease” that “causes weakness” in the skeletal muscles;

- Buerger’s Disease, a “rare” condition that causes “acute inflammation and clotting” of arteries and veins in the arms and legs;

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), or a long-lasting and “more serious” form of acid reflux, where the contents of one’s stomach come back up to the esophagus and can cause heartburn;

- Barrett’s Esophagus, a disorder in which the lining of one’s esophagus is damaged by stomach acid; and,

- “daily migraines” and spinal issues.

Here is an updated timeline on the president’s publicized health issues from March 2019 to March this year.

4. Who is responsible for informing the public?

Ople said the “burden” of disclosing the president’s health to the public in case of serious illness lies with the Office of the President (OP).

But the current OP claims not to have this information when responding to Freedom of Information (FOI) requests on the matter. (See Palace denies VERA Files’ FOI request on Duterte’s health; official statement, medical records ‘not on file’)

In October 2018, VERA Files requested from the office a copy of Duterte’s medical records, or an official statement on the status of his health, after he confirmed to have visited a hospital for an endoscopy and colonoscopy.

The OP ultimately said it was “unable to provide the sought information” because it was:

“…not among the records available on file nor in the possession of this Office…We shall gladly accommodate your request once the requested information becomes available for release.”

In his petition, de Leon said he sent an FOI request to the OP for Duterte’s “latest medical examination results” but was denied for the same reason. He said he asked the OP further when the information will be available but failed to get a response “despite repeated follow up.”

5. What happens if this provision is not followed?

When Ople was asked to clarify to the commission if a violation of Sec. 12, Art. VII would qualify as a “culpable violation of the Constitution, which is a ground for impeachment,” he said:

“In the sense that a constitutional standard was violated, I think that is perfectly a censurable act. But I am not inclined to say at this point that it attains to the level of a culpable violation.”

Source: Record of the Constitutional Commission Volume II, p. 459-460

Bernas said the intent of the provision is to “establish a principle,” which Ople confirmed.

Sources

ABS-CBN News, SC to tackle Duterte’s medical records, release of prisoners in 1st online session, April 15, 2020

Rappler, Supreme Court to hold first-ever virtual session on prisoner release, Duterte health, April 15, 2020

Manila Bulletin, SC justices hold special full court session on Friday, April 15, 2020

Dino de Leon Facebook account, Petition for Mandamus – De Leon vs. Duterte, April 13, 2020

Office of the Presidential Spokesperson, Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque’s Malacanang Press Briefing, April 14, 2020

Supreme Court, Justices, n.d.

Official Gazette, 1987 Constitution

Record of the Constitutional Commission Volume II, pp. 458-459

Official Gazette, Philippine Constitution – 1935, 1973

Bernas, J.G. (2011), The 1987 Philippine Constitution: A Comprehensive Reader

Ramos surgery

- Cambridge Dictionary, Carotid, n.d.

- New York Times, Surgery to Clear Artery for Philippine President, Dec. 23, 1996

- Asiaweek, The Country Skips a Beat, n.d.

- Los Angeles Times, President ‘Very Well’ After Artery Surgery, Dec. 25, 1996

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo 2006, 2009 health condition

- GMA News Online, Vice President: Arroyo illness a reflection of her hard work, July 27, 2006

- Gulfnews.com, Arroyo to go ahead with Spanish visit, June 24, 2006

- Fox News, Philippines President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo Hospitalized, June 22, 2006

- GMA News Online, Palace defends Arroyo: No breast repair, only benign lumps, July 3, 2009

- ABS-CBN News, Arroyo admits she has breast implants, July 3, 2009

- South China Morning Post, Arroyo admits to breast implants, a day after palace’s denial, July 5, 2009

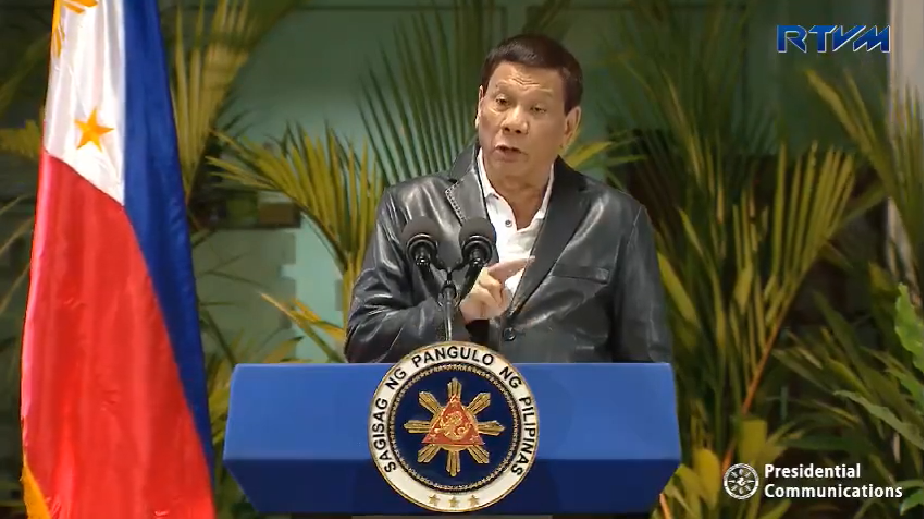

RTVMalacanang, Filipino Community Meeting (Speech) 10/5/2019, Oct. 6, 2019

United States National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Myasthenia Gravis Fact Sheet, n.d.

PTV, WATCH: President Duterte’s attendance to the PDP-LABAN campaign rally at Malabon City, April 2, 2019

Johns Hopkins, Buerger’s Disease, n.d.

Mayo Clinic, Buerger’s Disease, n.d.

RTVMalacanang, Peter Wallace Business Forum 12 12 16, Dec. 14, 2016

United States National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Acid Reflux (GER & GERD) in Adults, n.d.

United States National Library of Medicine, Barrett esophagus, n.d.

Timeline on Duterte’s health saga (March 2019 – March 2020)

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)