Road crashes are a leading cause of death

While COVID-19 cases continue to rise, road safety advocates say the country is also experiencing what they call a silent epidemic — injuries from road crashes. But unlike the response to the coronavirus pandemic, they say programs to protect road users, especially children, remain limited.

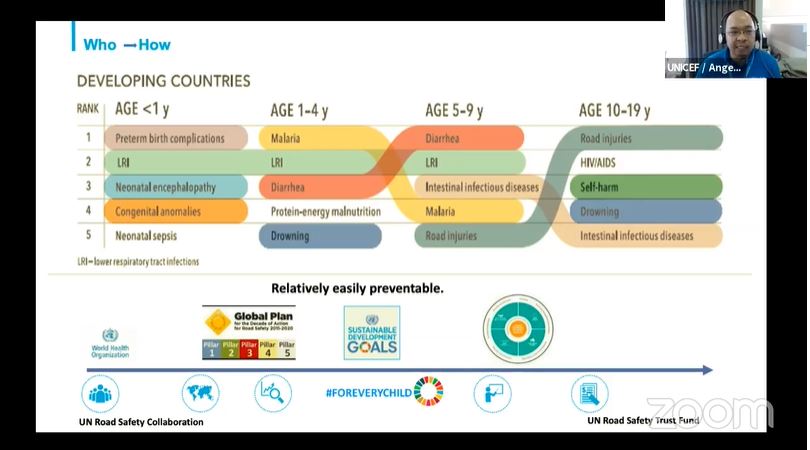

“Road traffic injuries are what we call a silent epidemic because many children die from it,” said Dr. Angelito Umali, program officer of United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) during the Ligtas na Daan sa Bata Ilaan (Safe Roads, Safe Kids) webinar on Sept. 15 organized la by the Philippine Legislators’ Committee on Population and Development (PLCPD).

According to the World Health Organization’s 2018 Global Status Report on Road Safety, road traffic injuries are the leading cause of death for children and young adults, aged 5-29. It estimates that 1.35 million people die annually due to road crashes.

In the Philippines, government data show at least 500 children die each year as a result of road crashes. The months-long lockdown to stem the spread of the coronavirus has kept people away from the roads, resulting in fewer crashes.

“While child road safety is a critical population and development issue as much as the COVID-19 pandemic, the former is a silent pandemic,” said PLCPD Executive Director Rom Dongeto. “But perhaps because it happens to individuals and groups in certain situations, as opposed to the extensive and indiscriminate effect of COVID-19, the latter sparks massive scare among the public, hence the government’s full attention to it,” he explained.

“As child road safety advocates, it is our duty to raise awareness on the issue to increase public support in order to elevate the discussion into a national concern and provide children with adequate protection,” Dongeto said.

Right now, UNICEF’s Umali pointed out, programs and policies focusing on children’s protection “remain limited.” He added: “We still don’t have a law to institutionalize road safety education, which could be a good way to reduce the number of child fatalities on the road.”

Road safety advocates say traffic injuries are a silent epidemic

Education key to changing behavior

In August 2019, Rebolusyonaryong Alyansang Makabansa (RAM) partylist representative Aloysia Lim filed the Road Safety Education Act of 2019 or House Bill 3402 to integrate road safety education in the K to 12 program.

The bill acknowledges that engineering solutions and innovations are not enough to reduce road fatalities and that education is key to changing road users’ behavior.

The bill calls for the establishment of an ad hoc committee that will analyze and plan what would be included in the proposed curriculum on how children can be safer on the roads.

The group will consist of members from the Department of Transportation, the Department of Education (DepEd), the Metro Manila Development Authority, the Land Transportation Office and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board.

“Most of the drivers, passengers and pedestrians – many of them do not remember or do not know their road safety rules. Accidents happen because the basic rules and traffic regulations aren’t given any worth. If we start teaching them young, as children through education, they will know road safety regulations better,” RAM’s Lim said during the webinar.

The bill is now pending with the House Committee on Basic Education and Culture.

Samuel Soliven of the DepEd’s curriculum development bureau, said at the same forum that some of their ongoing programs are “aligned with the bill.”

Davao, Cagayan Valley, and Bicol are among the areas where road safety materials and manuals on basic traffic rules are distributed to children in some schools, he said.

School zones not safe

There are existing regulations to address safety risks like speed limits around schools, Umali explained, but ironically, he said, “school zones have one of the highest risks of injury.”

He said that during one of their assessments on school safety, he recalls schools near national highways where cars were going faster than 50 kilometers per hour.

“When you are next to a national highway, where cars move really fast, and there is no pedestrian lane, children will have a more limited capability to ensure their safety so the risk increases,” the UNICEF official said.

Another factor why children often get involved in crashes is their limited physical capabilities.

“They cannot see the obstruction on the road due to their height. A possible scenario is they may not be able to see a car speeding behind another car. If the car behind overtakes the vehicle, the child could get hit. That is why school-going children must learn their limitations, and why they still need to be guarded. That’s also why we need traffic enforcers outside the school,” Umali said.

UNICEF’s child safety framework acknowledges that a desired outcome must sprout from a change in system and behavior.

“A change in system includes a proper implementation of policy, infrastructure, rules and regulations, while a change in behavior looks at teaching, such as how to use a sidewalk and a pedestrian lane,” said Umali.

“When we acknowledge the limitation of children, we will see more clearly why we need to teach road safety to children to safeguard themselves and to teach everyone as well to follow policies and road traffic rules, not just to avoid penalties, but to also save lives.”