BECAUSE the Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Networth (SALN) is a primary tool in checking the lifestyle of public officials and employees suspected of amassing questionable wealth, the new guidelines limiting access to it by no less than the Office of the Ombudsman is quite revolting.

The Office of the Ombudsman, formerly known as Tanodbayan, is an independent constitutional office responsible for investigating and prosecuting high government officials accused of graft and corruption, among other crimes. Hence, it is sometimes referred to as the “graft buster” in the bureaucracy.

Its website describes the Ombudsman and his deputies as “protectors of the people” who should “act promptly on complaints” filed against government officials and employees and “enforce administrative, civil and criminal liability” in every case where evidence warrants. This was meant to “promote efficient service” to the people, as ensured under Republic Act No. 6770, or the Ombudsman Act, and Section 12 Article XI of the 1987 Constitution.

But on Sept. 1, the Ombudsman issued Memorandum Circular No. 1 Series of 2020 that limits public access to copies of the public officials’ SALN under the custody of the Ombudsman. The memo was uploaded on Sept. 15 and will take effect on Sept. 25, or 15 days after it was published on Sept. 10 in The Manila Times.

In the new guidelines, SALNs can only be accessed by the official or a duly authorized representative, a requester acting on a court order in relation to a pending case, and field investigators of the Office of the Ombudsman for the purpose of conducting fact-finding investigation.

Members of the media and the public have been restricted from requesting copies of SALNs. Actually, Ombudsman Samuel Martires has already suspended since last year the processing of requests from the media for copies of SALNs for 2018. Because of this, President Duterte’s SALNs for 2018 and 2019 have not been released.

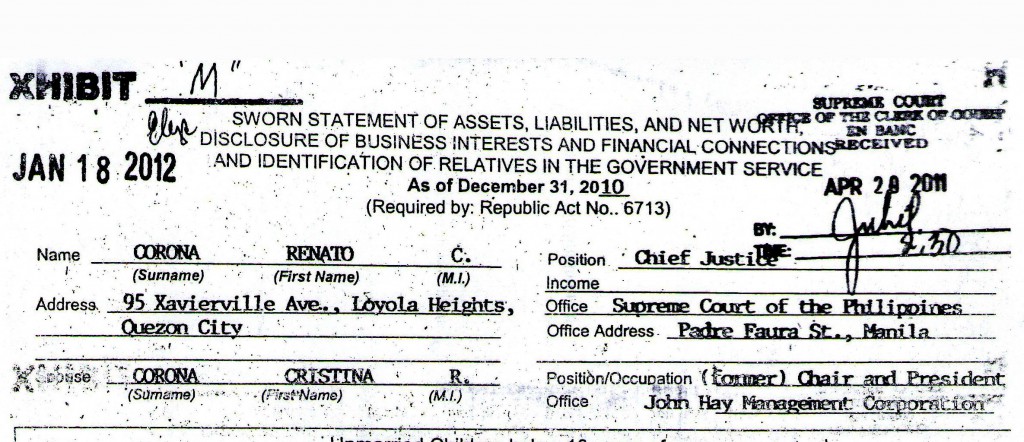

The Office of the Ombudsman is the repository of the SALNs of the president, vice president, and constitutional officials. The SALN contains information about personal properties such as real estate, investments, cash and bank deposits, business and financial interests, as well as relatives in government.

Through the SALN, it can be determined if an official declared increase or reduction in wealth and indebtedness while in public office.

The Ombudsman’s guidelines, however, run counter to the implementing rules of Republic Act No. 6713, or the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, which provides that the SALN “shall be made available for public inspection at reasonable hours.”

The same law, enacted in 1989 “to promote a high standard of ethics in public service,” spells out provisions for transparency and accountability as well as ethical behaviors in the performance of duties in government.

It likewise contradicts President Duterte’s Executive Order No. 2, issued in July 2016, entitled “Operationalizing in the Executive Branch the People’s Constitutional Right to Information and the State Policies to Full Public Disclosure and Transparency in the Public Service and Providing Guidelines Therefor.”

Under the new guidelines, a SALN copy may be requested for lifestyle check but the requester must file a verified complaint, with pieces of documentary evidence gathered against the person whose SALN is being requested attached, for appropriate action by an Ombudsman lawyer-evaluator.

It also requires that release of the SALN must have the consent of the official whose SALN is being requested. How could you expect an official suspected of underdeclaring or falsely declaring his assets to open his SALN for scrutiny?

The SALN is an important document that involves public interest as it contains information of public concern. Keeping it open for public scrutiny adheres to the constitutional principle of transparency and accountability in public office.

The Supreme Court already ruled in 2012 that custodians of SALN do not have authority “to prohibit access, inspection, examination, or copying of the [public] records.”

If further said that custodians of public documents such as the Office of the Ombudsman must not concern themselves with the motives, reasons and objects of the persons seeking access to the records. “The moral or material injury which their misuse might inflict on others is the requestor’s responsibility and lookout. Any publication is made subject to the consequences of the law,” it said.

In view of these reasons, the Ombudsman’s circular ought to be thoroughly reviewed, if not withdrawn altogether. Instead of promoting transparency, the Ombudsman’s circular helps cover up dishonesty through possible misdeclaration in the SALN which is kept away from public scrutiny.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.