President Duterte signs Republic Act 11479, also known as the Anti-Terror Act. Malacañang photo by Robinson Ninal, Jr.

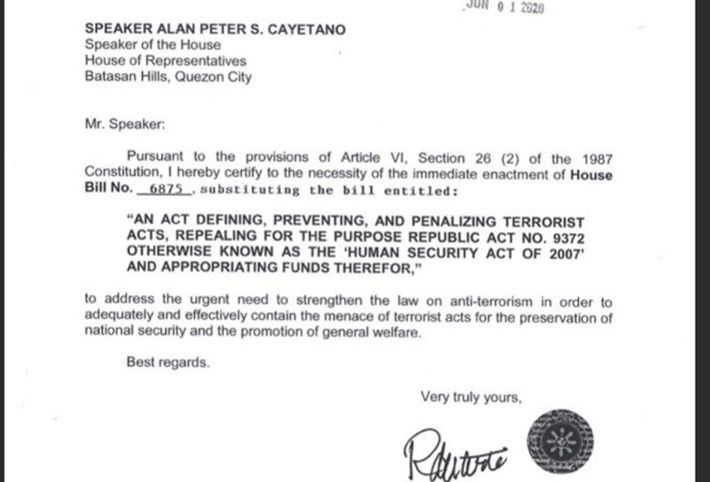

On July 3, 2020, President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law Republic Act (RA) 11479 or the Anti-Terrorism Act (ATA) of 2020. The measure he certified as urgent before Congress took effect on July 22. It is a long time coming, but the acts it fosters have long been part of an undercurrent of corrupt and repressive practices that drive state agents to go after their enemies with impunity. It is an achievement of those who have dreamt of a draconian internal security act even right after the 1986 Edsa Revolution.

At the tail end of his rambling statement on government’s response to the Covid-19 crisis that was aired around 1:00 a.m. of July 8, Duterte said: “Itong komunista [these communists] . . . they think that they are a different breed. They would like to be treated with another set of law. When as a matter of fact, they are terrorist [sic]. They are terrorist [sic] because we—I finally declared them to be one,” he said, noting that time he spent on he failed peace talks.

Besides the communists, he mentioned no other groups.

Though RA 11479 provides for administrative and judicial processes before an organization can be designated and then proscribed as a terrorist organization, the president’s personal indictment of communists as terrorists has set off alarms that the executive will use it to settle political scores.

A look back at the post-Edsa efforts to craft anti-terror legislation will lead one to the usual suspects — a generation of men in the police and the military with deep involvement in wiping out dissent to the Marcos dictatorship, achieving notoriety in the succeeding presidencies as part secretive security units often accountable only to the president.

Tracing their efforts to craft or influence internal security legislation will help show how intertwined – or confused – is the relationship between anti-terrorism and anti-subversion in the Philippines.

Battling Rebels and Terrorists: From Anti-Subversion to All-Out War

In 1957, RA 1700, or the Anti-Subversion Act, became law under the Garcia presidency. It outlawed the Communist Party of the Philippines—contemplating the party established in 1930 and what was referred to as its military arm, the Hukbong Mapagpalaya ng Bayan, “and any successors of such organizations”—penalizing affiliation or membership therein.

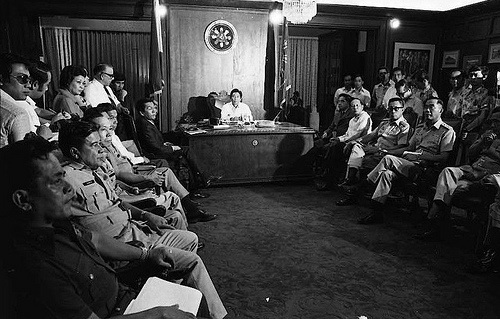

During his dictatorship, Ferdinand Marcos amended RA 1700 several times, and the explicit connection of subversion and terrorism in the country’s laws started.

In 1976, with Presidential Decree (PD) 885, he expanded its scope, proscribing “any association, organization, political party, or group of persons organized for the purpose of overthrowing the Government of the Republic of the Philippines with the open or covert assistance and support of a foreign power by force, violence, deceit or other illegal means.”

Via PD 1736 in 1980, Marcos further broadened the definition of subversive associations and organizations, and included “terrorism, arson [and] assassination” among the specified means of achieving their ends.”

President Ferdinand E. Marcos, Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile, and the military generals in the Presidential Study, Malacañan Palace. Photo from the Official Gazette.

With PD 1835, issued shortly before the paper lifting of martial law in January 1981, he brought the focus of the Anti-Subversion Law back to “the Communist Party of the Philippines and its military arm, the New People’s Army”—the Jose Maria Sison and Bernabe Buscayno-founded CPP-NPA—“and any such organizations/associations whose purposes are allied thereto.”

A final Marcos-era amendment, PD 1975, enacted toward the end of the Marcos regime in May 1985, removed confiscation of property and limited a previously broad provision on forfeiture of civil rights.

It was with the anti-subversion law and others such as the martial law General Orders and the 1983 Preventive Detention Action (PDA) law that the Marcos regime was able to incarcerate many political prisoners and commit the atrocities now recognized by the state via RA 10368, or the 2013 Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act.

A little over a year after Marcos was overthrown, President Cory Aquino repealed the decrees amending RA 1700, thereby restoring it to its 1957 state. Peace talks with the CPP-NPA-National Democratic Front (NDF) had by then collapsed in the wake of the January 1987 Mendiola Massacre, which was preceded by ceasefire violations on both sides. Two months later, in July 1987, Aquino issued Executive Order (EO) 276 that restored the focus of RA 1700 to the CPP-NPA-NDF. Cory had been seen earlier as being too soft on communists—releasing detained key members of the CPP-NPA-NDF including Sison himself. This resulted in one coup attempt too many by soldiers with strongly anti-communist sentiments or loyalists of Ferdinand Marcos, or both.

Cory Aquino generally hesitated to use her police powers, even when her government faced credible threats from both the Left and the Right. She did not want to appear to be following her predecessor’s footsteps. Her AFP vice chief of staff, Renato de Villa, however, was quoted during a hearing at the House of Representatives in September 1987 as saying that the country’s laws were “too lax on the insurgents.” In the same hearing, de Villa and Defense Undersecretary Fortunato Abat said that they wanted an internal security act similar to those in other Asian countries such as Singapore and Malaysia, to be enacted in the Philippines. Even after de Villa was later appointed AFP chief of staff, replacing Fidel Ramos who had been appointed defense secretary, nothing approximating an internal security act was enacted by the first President Aquino.

De Villa, Abat, and Ramos were all battle-tested key members of the Marcos-era defense/security establishment. De Villa became the first defense secretary of Cory’s elected successor, Ramos, in 1992. In September that year, Ramos enacted RA 7636, which repealed the Anti-Subversion Act.

But while the Ramos administration tried to solve insurgency via peaceful means, breakaway factions from both the CPP-NPA, such as the Alex Boncayao Brigade (ABB), and the Moro secessionists, mainly the Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG), continued to pursue their aims using what could be construed as terrorist tactics, including bombings, kidnappings, and executions, making their mark internationally via attacks on Americans in the Philippines.

In Policing America’s Empire, the historian Alfred W. McCoy argues that the roots of these so-called spoiler groups and outright crime syndicates can be traced back to failed attempts by the state to penetrate insurgent ranks – strategies that Cory Aquino put in effect as recommended to her by the police and the military.

The Red Scorpion Group had started as an “intelligence project” by the Philippine military to counter urban guerrilla warfare but quickly degenerated into Manila’s deadliest kidnapping gang, targeting wealthy Chinese. The Kuratong Baleleng Group was likewise launched as an anticommunist militia by the military before becoming notorious for its bank robberies. And Abu Sayyaf, a breakaway Muslim faction that the military formed to weaken Islamic separatist movements, soon morphed into a mercenary kidnapping ring in Mindanao feared by Filipinos and foreigners alike.

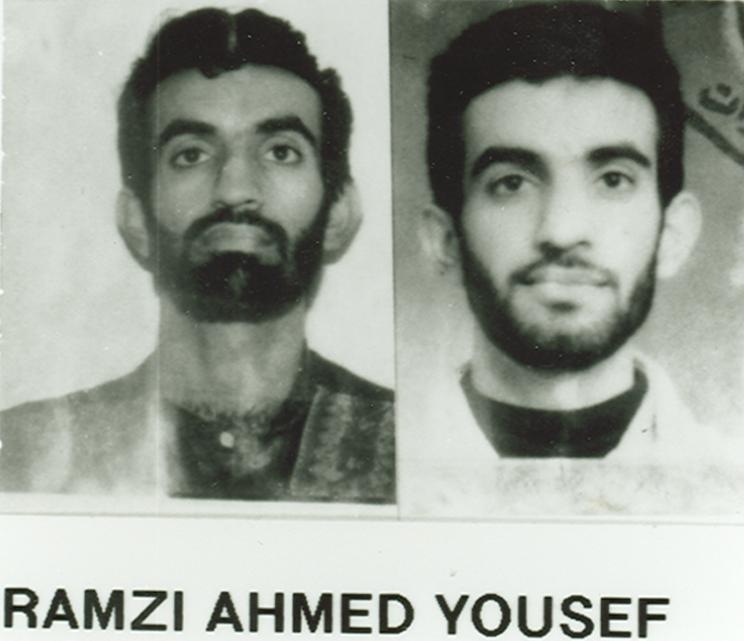

Added to this deadly and volatile mix was what was then referred to as international terrorism, foreigners operating in and from the Philippines to wage their global war. This was best exemplified by the likes of Ramzi Yousef, the Pakistani terrorist who was involved, among others, in the 1993 truck bombing of the World Trade Center in New York, and a plot to assassinate Pope John Paul II during his visit to the Philippines in 1995.

Incidents involving Ramzi Yousef, the Pakistani terrorist who was involved, among others, in the 1993 truck bombing of the World Trade Center in New York, and plot to assassinate Pope John Paul II during his visit to the Philippines in 1995 prompted then Sen. Orlando Mercado to file an anti-terrorism bill during the Ninth Congress to address international terrorism.

Such incidents prompted then Sen. Orlando Mercado to file an anti-terrorism bill during the Ninth Congress to address international terrorism. It sought to amend the Philippine Immigration Act of 1940 and target aliens like Yousef. Prior to the 1995 elections, the bill did not receive support from Malacañang.

After the 1995 midterm elections, Ramos issued EO 246, which reconstituted the National Action Committee on Anti-Hijacking—first established by Marcos in 1976 in the wake of a commercial aircraft hijacking that made international headlines—as the National Action Committee on Anti-Hijacking and Anti-Terrorism. In the EO’s “whereas” clauses, Ramos said terrorism has “indiscriminately caused great havoc,” destroyed lives and properties and caused ill effects to the economy. He said it was necessary to link up with other international agencies for the Philippines “to actively participate in the global crusade against terrorism.”

This emphasis on the global and international context of terrorism in the Philippines was what prompted President Ramos to call for a passage of an Anti-Terrorism Act in his fourth State of the Nation Address on July 24, 1995.

Later that year, an anti-terrorism bill drafted by the Department of the Interior and Local Government and the Department of Justice reached the Senate. As reported in the August 21, 1995 issue of the Manila Standard, this draft “included provisions that would authorize law enforcement authorities to open and look into bank accounts and to intercept communications of suspected terrorists through wire-tapping and other means.”

According to the article, in a hearing in August 1995 by the Senate Committee on National Defense and Security on the anti-terrorism bills, then DILG undersecretary Alexander Aguirre explained that the bill had completely new provisions necessary to combat terrorism, including one that “seeks to outlaw organizations which [seek] to advance their ideology, cause or purpose with the use of violence or any means of threat or intimidation to commit such violence.” The same article said DOJ Chief Prosecutor Nilo Mariano explained the bill wanted to give authorities the power to “inquire into bank accounts of suspected terrorists.”

During the hearing, several senators, including committee chair Mercado, stated their objections to the Malacanang draft. Among these senators was Juan Ponce Enrile, often referred to as the architect of the martial law regime. Enrile was quoted as saying he was inclined to reject the bill, citing “past experience” that “such techniques as wire-tapping were used by police/military authorities during the martial law regime [which] lead to human rights violations.”

Less than a year later, Enrile changed his tune. In January 1996, he filed his own anti-terrorism bill that, based on media accounts, closely resembled the draft of the executive branch. It was also said to contain provisions about warrantless arrests of suspected terrorists and the creation of “a six-man Anti-Terrorism Council [headed by the Secretary of Justice] which will coordinate, supervise, and monitor the efforts to the government to combat and eliminate terrorism.” Then Senator Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, a member of the minority “Conscience” bloc, was quoted as saying that the bill “smacked of martial law practices that should have already gone away with the dictatorship.”

Many echoed Macapagal-Arroyo’s sentiments, including the leadership of the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines. In light of this, Ramos publicly stated that he wanted Congress to prioritize the passage of social and economic reform measures over an anti-terrorism law. Macapagal-Arroyo welcomed this development, and was quoted by media as urging Ramos to completely abandon the bill.

Enrile continued to bat for the bill, citing a 1996 attack by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) in North Cotabato as a justification. Nevertheless, no anti-terrorism law was ever realized during the Ramos presidency. The MILF and the government formally agreed to a cessation of hostilities in July 1997. Fortunato Abat was at the helm of the government side of the negotiations leading to the peace treaty.

Later that year, on October 8, 1997, United States Secretary of State Madeleine Albright released the first US Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) list, which included thirty organizations, including the Abu Sayyaf.” The main effect of inclusion in the US FTO list is US financial institutions may block transactions involving assets of listed terrorist organizations.

Still in 1997, Abat became Secretary of Defense vice De Villa, who left Ramos’ cabinet to run for president in the 1998 elections. Both de Villa and Enrile became also-rans in the election that made Ramos’ vice president, Joseph Estrada, the country’s chief executive.

Estrada campaigned partly on an anti-crime platform, capitalizing on his designation as chair of Ramos’s Presidential Anti-Crime Commission (PACC). Among those Estrada recruited to join him in the PACC was then Laguna provincial police director Panfilo Lacson, a former member of the dreaded Marcos-era MISG. When Estrada became president, Lacson became head of PACC’s successor, the Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Task Force (PAOCTF), and later chief of the Philippine National Police.

When Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo took over the presidency from Estrada, Lacson’s enemies within the police exposed his alleged illegal surveillance operations through PAOCTF’s Special Directorate X (SDX). In August 22, 2001, the Philippine Daily Inquirer reported that the police seized data and equipment used to surveil “cellular phone calls of senator-judges, House prosecutors and opposition figures during Estrada’s [impeachment] trial.”

The Estrada administration continued to face defense and security problems that besieged its predecessor—such as the ASG, the ABB, and the CPP-NPA. Estrada infamously chose to exercise his police and commander-in-chief powers to address them, including resuming the campaign against the MILF. Peace talks with both the Moro secessionists and the CPP-NPA-NDF stalled during Estrada’s brief presidency.

Despite a string of attacks in 2000 by the Abu Sayyaf, MILF, ABB and the Rizal Day Bombings by the transnational extremist group Jemaah Islamiyah, Estrada did not ask Congress to pass an anti-terrorism law.

On January 5, 2001, Estrada issued EO 336, reconstituting the National Action Committee on Anti-Hijacking and Anti-Terrorism as the National Council for Civil Aviation Security, partly due to “the threat of terrorism against civil aviation directed terrorism.” By that time, his impeachment trial at the Senate was in full swing. Within days after the trial broke down over a refusal by the majority in the Senate to examine a particular piece of evidence, Estrada was ousted via the so-called Second Edsa Revolution or “Edsa Dos.” Riding on a wave of dissent from various sectors, then vice president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo rose to the presidency on January 20, 2001.

Hunting the Terrorists, Ravaging the Left: Anti-Terrorism Laws and the US-led Global

It was not long before Macapagal-Arroyo had to deal with the security threats that plagued her predecessors. On May 22, 2001, a small armed group launched a nighttime attack on the Pearl Farm Resort in Samal Island in Davao del Norte, resulting in the death of two of the resort’s employees. Four were taken hostage, all of whom were able to escape while the army chased down, and later engaged, what they claimed to be “local bandits.” The raiders were eventually confirmed to be members of the Abu Sayyaf Group.

Then in the early morning of May 27, 2001, the ASG kidnapped staff and guests at the Dos Palmas Resort in Palawan, including American missionaries Martin and Gracia Burnham. Six days later, with their hostages in tow, the ASG took over a church and a hospital in Lamitan, Basilan. The 103rd Infantry Brigade engaged them. Four hostages were able to escape. What has since been dubbed the Lamitan Siege ended with the ASG escaping with their hostages, including new ones.

Reacting to the May 27 kidnappings, Macapagal-Arroyo said in a televised address that she would meet “force with force” and “arms with arms.” She reiterated the government’s “no ransom” policy. Before the Abu Sayyaf slipped away from Lamitan, she said in another

broadcasted address on June 2, 2001 that the “bandits” had been cornered, and that they should surrender and release their hostages; “Isang bala na lang kayo,” she boldly declared.

It would take a year before the hostage-taking ended with a military rescue mission. Two hostages died in the crossfire: Martin Burnham and Ediborah Yap, a nurse captured during the Lamitan Siege.

Besides the ASG and the continuing prosecution of Estrada for plunder, the banner headlines of newspapers from June to early September 2001 were also focused on alleged illegal activities of Lacson during his tenure as head of PAOCTF, as brought to the public’s attention via the head of the Intelligence Service of the AFP, soldier turned NPA turned soldier again, Victor Corpus.

Then, the world’s attention was captured by the attacks on the United States, which brought down the World Trade Center’s twin towers and killed thousands, on September 11, 2001.

The US-led “Global War on Terror” was subsequently launched. Besides participating in the invasion of Afghanistan in the effort to get Osama bin Laden, leader of the transnational extremist group Al-Qaeda, many countries started to propose laws overtly meant to address terrorism. The Philippines followed suit.

On November 5, 2001, then Ilocos Norte representative Imee R. Marcos, the dictator’s eldest daughter, filed a bill for “An Act Defining Terrorism, Providing Penalties Therefor and for Other Purposes.” About a month before she filed her anti-terrorism bill, she delivered a privilege speech wherein she questioned Macapagal-Arroyo’s “all-out support” for the War on Terror, wondering if the Philippines was at an actual state of war and thus allowing more American military intrusion in the country.

Her first anti-terrorism bill was later substituted by an identically titled one on April 4, 2003 that proposed to “bring the crime of terrorism within the coverage of the Anti-Wire Tapping Law and the Anti-Money Laundering Law.” It called for creation of “an Anti-Terrorist Action Council to coordinate, supervise and monitor the counter terrorism efforts of the government.”

U.S. President George W. Bush welcomes President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo to the Oval Office Tuesday, June 24, 2008, at the White House. White House photo by Eric Draper.

Macapagal-Arroyo certified that bill as urgent on May 5, 2003, after another rash of deadly bombings in Mindanao in March and April 2003 in a city that until then had been considered relatively peaceful: Davao City, then governed by Mayor Rodrigo Duterte. The attacks prompted Macapagal-Arroyo to declare a “total war” on terrorism and a state of lawless violence in Davao, deploying of hundreds of soldiers in the city.

Before then, Duterte’s Davao had reportedly been a “safe haven” for the various armed groups in Mindanao, including the Moro secessionists and the NPA. According to Carlos Isagani Zarate, in an article published on April 13, 2003 in the Inquirer, Duterte even openly invited members of rebel groups, including the bandit group Abu Sayyaf, to have their ‘R&R;’ [rest and recreation] in the city “for as long as the city is spared any violent incident or skirmish.”

Macapagal-Arroyo appointed Duterte to be an anti-crime consultant in 2002. But the president did not share the mayor’s accommodationist views. Her term is remembered partly for a brutal anti-insurgency campaign targeting the CPP-NPA called Oplan Bantay Laya, spearheaded by the likes of Major General Jovito Palparan. Macapagal-Arroyo also took to calling the CPP-NPA a terrorist organization. She even successfully lobbied for their inclusion in the US FTO list on August 9, 2002, and in the terrorist lists of Australia and European Union on October 28, 2002.

At a press conference in February 2002, the president was also quoted as saying that those opposing the RP-US “Balikatan” exercises later that month were “not Filipinos” and were “Abu Sayyaf lovers.”

By July 2002, after the Balikatan exercises ended, Macapagal-Arroyo truly trained her sights on the CPP-NPA. As reported by the Inquirer on August 6, 2002, the president “ordered the Department of National Defense and the [AFP] to move troops from Abu Sayyaf-influenced areas in Mindanao to places where the [NPA] is operating” since, according to press secretary Ignacio Bunye, the ASG “problem” had been “effectively addressed.”

Days after the inclusion of the CPP-NPA in the FTO list, an August 12, 2002 article in the Manila Standard cited a defense department source as saying the government was trying to pull the plug on the CPP-NPA’s local and foreign funding sources using the Anti-Money Laundering Act approved by the president in September 2001. In an Associated Press report published by the Standard on August 18, 2002, National Security Adviser Roilo Golez claimed that they had started freezing the funds of the CPP-NPA’s “front organizations.”

“For the longest time, we have always regarded the NPA as a terrorist group. They’re the number one source of terrorism in the Philippines,” then Executive Secrtary Eduardo Ermita was quoted as saying in a December 8, 2005 article in the Philippine Star. At the time, Ermita also the head of an Anti-Terrorism Task Force formed by Macapagal-Arroyo before the 2004 elections.

In 2004, Macapagal-Arroyo gained a full six-year term as president in an election marred by accusations of massive fraud. Using gains from aligning with the United States in its global war on terror, Macapagal-Arroyo utilized funds, arms, and diplomatic support not so much to conduct a full frontal war with the CPP-NPA, but a campaign of terror aimed at activists that she and her military advisers believed to be supporters of armed insurgents. In December 2006 Macapagal-Arroyo launched Oplan Bantay Laya II, a three-year plan to simultaneously crush the CPP-NPA, the MILF, the Abu Sayyaf and Jemaah Islamiyah.

“Arroyo’s all-out war proclamation,” Paz Verdades M. Santos noted in Primed and Purposeful: Armed Groups and Human Security Efforts in the Philippines, “has been criticized as a ploy to quell military restlessness, since a battle against the Communists will keep the army busy and provide a rationale for distributing awards and largesse to the officers.” Ever since the 2003 Oakwood Mutiny by junior military personnel protesting incessant charges of corruption in her administration, Macapagal-Arroyo had been keeping a close eye for any restive factions within the military.

Her administration’s strategy for survival and facade of a “Strong Republic,” was paid for in blood by hundreds of activists who became victims of extrajudicial killings. Killers riding in tandem in a motorcycle entered the popular imagination.

As pointed out by Alfred W. McCoy, “Under the umbrella of an operation that bundled communist and terrorist targets, the military mobilized some fifty vigilante groups nationwide with the aim of cleansing half the NPA guerrilla zones during 2007. Over time this fusion of vigilante violence and military murder started to resemble the low-intensity conflict doctrine that U.S. military advisers had introduced to counter communist guerrillas in the late 1980s.” Independent fact-finding bodies like those led by former Supreme Court Justice Jose Melo and UN special rapporteur for human rights, Philip Alston, documented this grim reality.

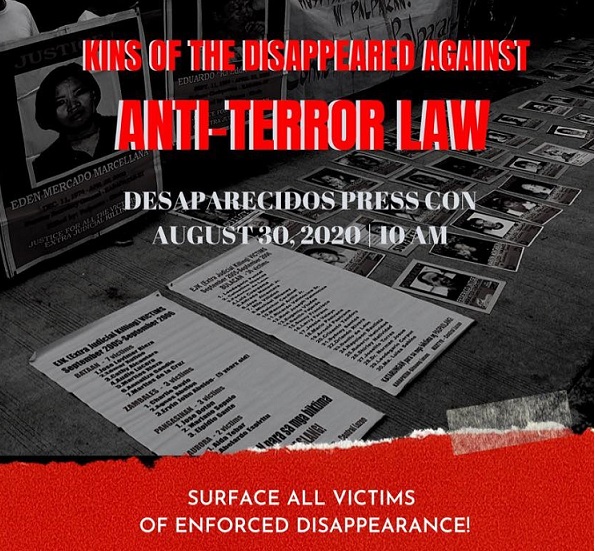

The direness of the situation even prompted the Supreme Court then led by Chief Justice Reynato Puno to promulgate the writ of amparo that he said “serves both preventive and curative roles in addressing the problem of extralegal killings and enforced disappearances.”

In most cases, the writ of amparo, if granted, orders the police and the military to cease their interference in a person’s life, stop surveillance and release those unlawfully detained. Thorough investigation on enforced disappearances must be made under close supervision of the court, which can hold the police and military accountable for human rights transgression. Since 2007, however, only about seven cases involving writ of amparo have been affirmed by the Supreme Court. This limited application is expected to be weakened further with the ATA in effect.

Interestingly, the principal author of the anti-terrorism bill in the House at the time apparently did not share the view that the CPP-NPA were terrorists. In a speech on November 18, 2002, Imee Marcos noted that communist rebels “have consistently selected political and military victims, arguably rendering them subject to the laws of war, belligerence and the Geneva conventions.” In the same speech, she outlined key features of her anti-terrorism bill, which, despite being certified as urgent by the president, was not approved during the Twelfth Congress.

Marcos would be elected to her third consecutive term in the House in 2004. Enrile was also reelected as senator. Marcos refiled her anti-terrorism bill that year, in the shadow of the deadliest marine attack by a terrorist group, the February 27, 2004 bombing of SuperFerry 14 in Manila Bay, perpetrated by the Abu Sayyaf. US pressure to pass an Anti-Terrorism law, already strong given the Dos Palmas incident, continued to mount.

The House consolidated bill, HB 4839, with Marcos still principal author, was finally approved by the House on April 4, 2006. It listed ten ways that terrorism can be committed, defining terrorism as “the premeditated threatened or actual use of violence or force or any other means that deliberately tend to cause or actually cause harm to persons, or of force and other destructive means against property or the environment, with the intention of creating or sowing a state of danger, panic, fear or chaos to the general public or segment thereof, or of coercing or intimidating the government to do or refrain from doing an act.” It contained provisions on terrorist financing, proscription of organizations, wiretapping, and the creation of an Anti-Terrorism Council chaired by the executive secretary and vice-chaired by the national security adviser. Detention after warrantless arrest was also permitted, strictly based on existing laws, and not exceeding three days.

National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr. talks with President Duterte before the start of the joint Armed Forces of the Philippines-Philippine National Police Command Conference in Malacañang on December 12, 2018. Also in the photo are Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea and Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana. Malacañang photo by Simeon Celi, Jr.

In the Senate, five anti-terrorism bills were filed in 2004. These were consolidated and substituted by SB 2137, filed on October 12, 2005. Villar, the main sponsor, gave way to Enrile as main proponent after the latter filed yet another anti-terrorism bill on January 9, 2006.

At around the same time, Macapagal-Arroyo was embroiled in human rights controversies. On Feb. 24, 2006, she issued Proclamation 1017 declaring a state of national emergency due to an alleged leftist-rightist conspiracy to topple her government. Her General Order No. 6 directed the head of the military to coordinate with the police chief and other law enforcement agencies to “undertake such actions as may be necessary to prevent and suppress lawless violence.” PP 1017 and GO 6 were in effect for a week, during which the police forcibly dispersed and arrested some of the left-leaning protestors peacefully commemorating the first Edsa Revolution and raided the office of the opposition-associated Daily Tribune.

On the same day that Enrile became the anti-terrorism bill’s main sponsor, five members of the Union of the Masses for Democracy and Justice—supporters of Estrada—were taken and detained by the ISAFP. The Intelligence Service claimed that the “UMDJ-5” were identified as coup plotters colluding with the NPA. The charge was never proven. One of those arrested claimed that he was tortured while detained.

Such incidents made their way to Senate deliberations on the anti-terrorism bill and discussions of the defense budget. Lacson repeatedly stated that he was for an anti-terrorism law, but that he did not trust Macapagal-Arroyo with it, noting the UMDJ-5 issue.

During his interpellation on August 1, 2006, Lacson again expressed his “misgivings” about having the law passed during the Macapagal-Arroyo administration, given the praise she heaped during her State of the Nation Address on Maj. Gen. Palparan for his anti-insurgency campaign, despite the accusations of him bearing the responsibility for numerous extrajudicial killings of activists. On September 17, 2018, Palparan was among those convicted at the Malolos Regional Trial Court for the kidnapping and serious illegal detention of Karen Empeno and Sherlyn Cadapan in June 2006.

In many ways, SB 2137 was similar to the version passed by the House, though there were also key differences. For instance, the 2006 Senate bill wanted the president to be the chair of the Anti-Terrorism Council instead of the executive secretary; they both agreed to make the national security adviser the ATC’s vice chair. Both also criminalized membership in a formally proscribed terrorist organization.

Neither of these provisions made it to what became RA 9372, or the Human Security Act. Senator Franklin Drilon argued against criminalizing mere membership, saying that the previous law that penalized membership in illegal organizations, the Anti-Subversion Act, was already repealed. Meanwhile, it was Senator Aquilino Pimentel Sr. who suggested that the president be removed from the Anti-Terrorism Council, and that the Secretary of Justice be made the council’s vice chair.

Drilon and Pimentel made numerous amendments to the bill—including many safeguards against abuse—most of which were accepted by Enrile. Pimentel can be credited with the most amendments, including changing the short title of the law from the Anti-Terrorism Act to the Human Security Act.

Based on the Senate journal, Sen. Jinggoy Estrada was responsible for the provision of the HSA that allowed the Commission on Human Rights “concurrent jurisdiction to prosecute public officials, law enforcers, and other persons who may have violated the civil and political rights of persons suspected of, or detained” for the crimes listed in the law. Pimentel said the senators also agreed to move the effectivity date of the law to two months after the May 2007 elections to “prevent people in power from taking advantage of the Anti-Terrorism Act to harass or cause harm to their political opponents.” Such was their supposed distrust of the Macapagal-Arroyo administration.

Only two senators voted against the bill: Jamby Madrigal and Mar Roxas. After a brief bicameral conference on February 7, 2007 to reconcile differing provisions, the House adopted the Senate version of the bill in toto. Macapagal-Arroyo, via Proclamation No. 1235, called a Special Session of Congress on February 19-20, 2007, asking for passage of numerous bills, including the Anti-Terrorism Act.

The bicameral version was swiftly ratified in the House during the Special Session. One of the representatives who voted against the bill’s enactment was Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III, who was then running for senator. The bill was sent to the president for signature on February 27, 2007. Macapagal-Arroyo enacted it a week later.

Foreign governments, such as those of the United States and Australia, congratulated the Macapagal-Arroyo administration for passing the law and for demonstrating commitment to implement comprehensive counter-terrorism measures. One must note that, until now, no foreign government has issued a statement supportive of the ATA of 2020.

The HSA’s enactment was also met with street protests. Macapagal-Arroyo had to assure the public that the law was “against bombers and not protestors.” Leftists nevertheless considered the law draconian and a threat to democracy. Even Senator Pimentel, despite the safeguards he introduced, still thought that the law was prone to abuse.

And they were right. On March 21, 2008, farmer Edgar Candule of Botolan, Zambales was arrested without a warrant on suspicion of being a member of the NPA. At Camp Conrado Yap in Zambales where he was detained for three days without counsel, tortured to confess that since he was a member of the NPA, a terrorist organization, he is a terrorist who can be prosecuted under the HSA. Three years later, the Zambales Regional Trial Court dismissed that case against Candule. As per a provision in the HSA, since he was wrongfully charged and imprisoned, he must be awarded PHP 480.5 million in damages. Nothing was heard of again about this case since 2010 or whether Candule was duly indemnified or not.

Despite the fear and fanfare that attended the passage of the law, many recognized early on that it was a difficult law to implement. The Manila Times on July 1, 2007, quoted a recently reelected Senator Lacson as saying that the HSA had “too many safeguards”—about 168, by the senator’s count—and that he was keen to file a bill to reduce them. Even Senator Drilon was quoted by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, on the day of the law’s signing, as saying “the law is toothless.”

By October 2007, the president also made clear that she wanted the HSA “strengthened.” She told a group of businessmen that to make the HSA more effective, “we are working with Congress on a bill to make the illegal possession of explosives nonbailable, with ample safeguards and penalties against planted evidence,” according the October 27, 2007 issue of the Manila Times. The same article quoted National Security Adviser Norberto Gonzales as saying that the HSA was “hard to enforce” and that “as the law stands, law-enforcement agencies could resort to existing laws to prosecute certain specific violations that could be defined as part of an act to overthrow the government,” likely alluding to the country’s subversion and rebellion laws.

In a confidential Department of State cable dated June 13, 2007 uploaded on Wikileaks, Gonzales was described as telling a visiting US official that the HSA “would be ineffective against the NPA.”

By late 2007, it seemed clear that the administration did not see the HSA as being useful versus the communists. As quoted by the Philippine Daily Inquirer in December 15, 2007, then AFP Chief of Staff Hermogenes Esperon believed the country needed something that would “approximate the internal security act of other countries [that are using it] as a tool in eradicating or defeating insurgency in their homelands.” Esperon was keeping alive de Villa and Abat’s dream of a repressive internal security act.

The article said Esperon believed that repealing the Anti-Subversion Law “allowed the NPA to thrive.” Regarding the HSA, Esperon believed that the law’s safeguards, such as the hefty fine meant to deter illegal detention, had “[deprived them] of rapidity that, of course, should go with the usual caution.”

Both critics and a few administration allies, including then Senate president Manny Villar, decried the possibility of the Anti-Subversion Law’s revival. By then, the Senate was dominated by members of the opposition, and public approval of Macapagal-Arroyo was steadily declining. No anti-subversion law or amendment to the HSA was passed during the rest of her term.

The Insecurities of the Human Security Act and the Brute Force of the Anti-Terror Law

The HSA was also not amended during the term of President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo’s successor, Noynoy Aquino. But not for lack of trying; on the eve of the tenth anniversary of 9/11, executive secretary and Anti-Terrorism Council chair Paquito Ochoa released a statement, saying that certain provisions of the HSA needed to be changed. Among them was the removal of the provision requiring suspected terrorists to be informed that they are under surveillance, and the reduction of the 500,000/day fine of wrongful detention of a suspected terrorist upon acquittal. Ochoa however clarified that other safeguards against maltreatment in detention need to be added.

However, Aquino did enact RA 10168, or the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act of 2012. RA 10168’s relatively swift and uncontroversial passage may be attributed to the fact that it was overdue, as a fulfillment of the Philippines’s ratification of the International Convention for the Suppression of the Financing of Terrorism on October 14, 2003. It made terrorism financing a standalone offense. Moreover, it made proscription under Section 17 of the HSA more consequential. Through RA 10168, it became a crime within the Philippines to financially support court-proscribed organizations.

On September 7, 2015, the ASG was finally proscribed under the HSA by the Isabela City Regional Trial Court in Basilan, upon application by the Department of Justice, then headed by Leila de Lima. It was the only group to be formally proscribed under the HSA.

The second President Aquino also had to face numerous national security threats besides the ASG. Among these were the Nur Misuari-led MNLF faction which led a two-week Zamboanga Siege in September 2013, and the Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters (BIFF), the MILF splinter group that harbored Malaysian terrorist Marwan. The killing of Marwan by members of the PNP Special Action Forces was marred by a “lack of coordination” with the AFP and the MILF, leading to the infamous Mamasapano Clash on January 25, 2015. The former event was tied to Misuari’s perception that the MNLF was being sidelined as the MILF was close to settling a final peace treaty with the government. The latter event was seen as a setback in implementing the signed treaty, the Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro. The law creating the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region was enacted only in July 2018.

As for the CPP-NPA-NDF, like his post-Edsa predecessors and his successor, Aquino engaged in peace talks, which were unsuccessful. It led to a bloody counterinsurgency campaign, this time called Oplan Bayanihan. Nevertheless, there were some who thought that, like his mother, Noynoy Aquino was somewhat soft on the CPP-NPA. For one, during his term the military veered away from tagging the CPP-NPA-NDF as “communist terrorist group,” replacing the term with “CNN,” an initialism of CPP-NPA-NDF.

An earlier incident also supposedly led to demoralization of members of the Philippine Army. Health workers suspected of being members of the NPA were arrested in Morong, Rizal in February 2010. Noynoy Aquino ordered the “Morong 43” released in December 2010, citing lack of due process. According to a GMA News Online article published on December 12, 2010, then Army spokesperson Col. Antonio Parlade claimed soldiers’ morale was affected by the president’s decision.

Parlade graduated from the Philippine Military Academy in 1987. He would later be educated at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, where he produced a thesis titled “An Analysis of the Communist Counterinsurgency in the Philippines” in 2006. In his thesis, he referred to the CPP-NPA as CTM, or Communist Terrorist Movement. He claimed that political warfare is the CPP-NPA’s primary line of operation and it has since managed to send 15 sectoral representatives to Congress. The representatives Parlade referred to were the members of the Makabayan Bloc, which the Macapagal-Arroyo administration had unequivocally called “legal fronts” of the “communist terrorist group.”

While Aquino himself refrained from such rhetoric, the effects of Oplan Bayanihan, the Mamasapano Clash, and other issues led to the Makabayan Bloc initially supporting another presidential bet, Senator Grace Poe, instead of Aquino’s anointed “presidentiable,” Mar

Roxas, in the 2016 elections. But as the polls drew to a close, the Makabayan Bloc openly threw their support behind the elected president, Rodrigo Roa Duterte.

President Duterte gives a warm welcome to Moro National Liberation Front Founding Chairman Nur Misuari at a meeting in the Malacañang on March 19, 2019. Malacañang photo by Ace Morandante.

Duterte tried applying his accommodationist strategy in Davao on a national scale, welcoming Misuari in Malacañang several times, appointing NDF-designated Cabinet members (all later rejected by the Commission on Appointments) and even requesting the delisting of the CPP-NPA from the US FTO list (rejected by the US) — all gestures meant to show sincerity in reaching a peace accord with the communists. However, peace talks again broke down, what with poorly implemented ceasefires and mounting criticism against Duterte’s War on Drugs.

The AFP took to calling the CPP-NPA-NDF as the “Communist Terrorist Group” again. On December 5, 2017, Duterte issued Proclamation 374, declaring the CPP-NPA as a terrorist organization, which, does not hold water under the HSA and RA 10168. Perhaps realizing this, then justice secretary Vitaliano Aguirre filed a petition on February 21, 2018 at the Manila Regional Trial Court for proscription of the CPP-NPA under the HSA. The petition remains pending.

By December 2018, Duterte signed Executive Order No. 70, creating the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict, chaired by his national security adviser, Macapagal-Arroyo’s old hand, Hermogenes Esperon. One of NTF-ELCAC’s most visible faces has been Parlade, also currently the commander of the Southern Luzon Command.

In the bills filed by Senators Lacson, Tito Sotto, and Imee Marcos for a law overhauling the HSA in the current Congress, the justification was the five-month long conflict in Marawi in 2017 between government forces and the local allies of the Islamic State group.

But from the public pronouncements of the president; Esperon, Parlade, and others in the NTF-ELCAC and their propagandists, it seems understood that the new Anti-Terrorism Act will also serve the function of an anti-subversion/internal security law. The ATA seems to be the fulfillment of a decades-long dream of law enforcers and the military to be as minimally fettered by the 1987 Constitution in battling the communist insurgency and political dissent marked as terroristic acts.

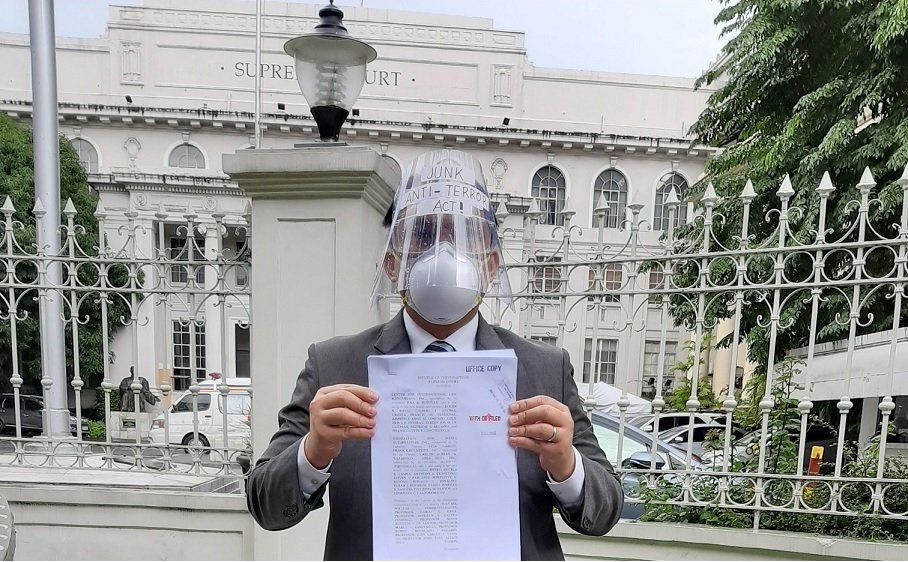

As of this writing, at least 27 petitions assailing the ATA on various grounds have been filed before the Supreme Court.

“The ATA vests the ATC [Anti-Terrorism Council] with powers akin to but greater than the President’s powers under the Commander-in-Chief Clause, in the process evading constitutional limitations,” warns former Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio and his colleagues in their petition challenging the ATA. This is a law that will create a cabal within the executive branch which in the end might succumb to the idea that they are a power unto themselves.

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Larah Vinda Del Mundo and Elinor May K. Cruz provided assistance in writing this report.)