A “cure” of legislative measures and police crackdowns could be worse than the actual “illness” of disinformation itself, cautioned a new study that looked at the regulation of disinformation during the 2019 polls in three Southeast Asian countries, including the Philippines.

A multi-pronged approach of seeking accountability from technology platforms, regulating official and unofficial online election campaigns, and civil society organizations targeting the networks behind disinformation can help in governance of digital election-related content, according to the study “Mitigating Disinformation in Southeast Asian Elections: Lessons from Indonesia, Philippines and Thailand,” launched Wednesday, May 20, by the NATO Strategic Communication Centre of Excellence.

“Despite regularly declaring themselves as ‘victims’ of online negative campaigning and disinformation production, the state, political parties and politicians have also increasingly become key funders of the industry, exacerbating the problem, but at the same time arguing for new laws and regulations around social media which ultimately crack down on broader freedom of expression,” according to researchers Jonathan Ong, associate professor of global digital media from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Australia National University senior lecturer Ross Tapsell.

The study shed light on how state actors have participated in the production of disinformation in the Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand, and warned how existing defamation, libel and cybercrime frameworks have been used to control social media conversations and “create chilling effects on free speech.”

Indonesia, for example, saw during its elections in April last year the arrest of people who created disinformation material against President Joko Widodo on the basis of a 2008 law designed to monitor online commentary.

On the other hand, social media in Thailand, which held polls in March 2019, was extensively monitored by the military and “teams of cyber scouts,” where enforcement of the “Computer Crime Act” has led to the arrest of at least five people for “sharing falsehoods and endangering national security.”

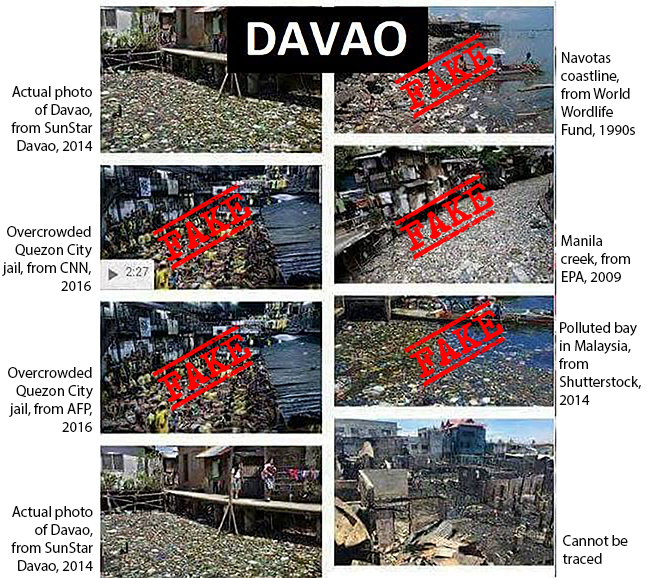

While the Philippines does not have a law against online disinformation, the research pointed out that the Philippine government has used state apparatuses to “target vocal critics and journalists,” such as state actors “propagating an Oust Duterte plot” a month before the 2019 midterm polls.

Outside government regulation, the study also looked at how disinformation in the three countries is being addressed by local election commissions and social media giants, the latter having its platforms largely being used to propagate falsehoods and hate speech.

It noted that while the Philippines election commission has implemented a new rule for candidates to disclose social media campaign spending, it will have little to no impact “without efficient monitoring of actual and ‘unofficial’ digital campaigns.”

Meanwhile, Thailand was reported to have a very partisan elections commission, “with rules arbitrarily applied targeting only opposition candidates.”

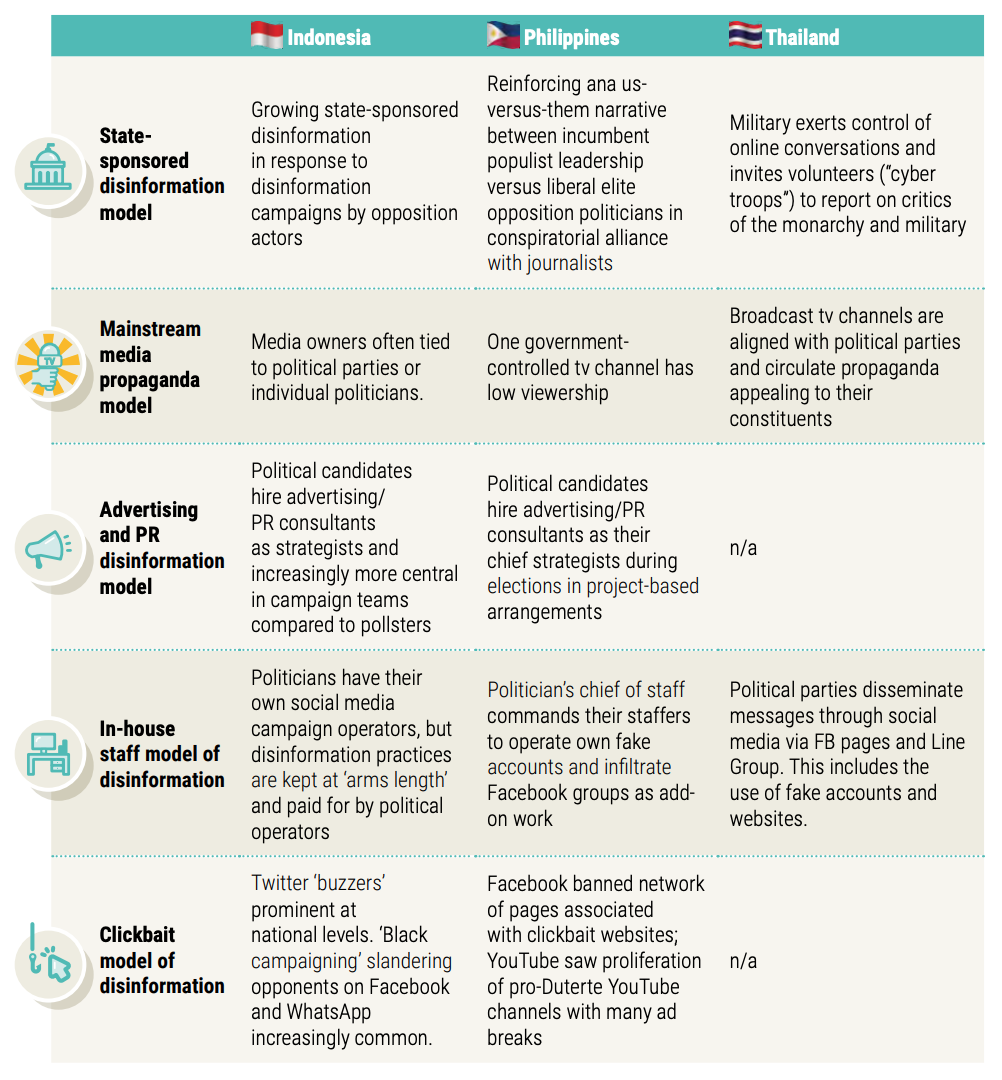

Apart from regulation, the study also sheds light on how disinformation has been “diversified” and “democratized.”

“[A] wider range of political actors and parties enlisted a diversity of digital campaign specialists and paid out “buzzers” (Indonesia), “trolls” (Philippines), and “IOs (information operations)” (Thailand) circulate manipulative narratives discrediting their political opponents,” the researchers said.

The researchers identified five key models of disinformation that it saw being employed not just by incumbents but also other key election players such as opposition parties. It has also evolved from just grassroots “black market” operations to now also involving PR “boardrooms.”

The study seeks to provide valuable information on election-related disinformation and its regulation for other countries to also learn from Asian experiences.

“The three countries can certainly learn from each other the range of possible regulatory interventions that can be applied,” Ong said in a NATO StratCom press release on the study.

“Clearly, disinformation is a systemic problem that cannot be eradicated by fact checks or high-publicity platform bans of individual ‘bad actors’ alone. Nor can government legislation be fully trusted with legislation as they can hijack “fake news” panics to target critics and dissenters.”

The full study can be accessed here.