VERA Files is 10 years old.

To mark our 10th anniversary, we are reposting 10 stories that mirror the group’s interest and commitments.

This story was first published on June 20, 2017.

(Second of three parts. Read the first part here.)

Tanay, Rizal— By its passengers’ accounts, there was something wrong with Panda Bus No. 8.

Halfway through their 90-kilometer journey from Quezon City to Tanay, Rizal, those seated at the back could already smell something burning. And on the road leading to where it crashed, killing 15 people, investigators found no skid marks, indicating the wheels hadn’t stopped turning until the final moment.

The initial report of the Tanay police said, “… the bus accordingly suffered from brake defects and lost its control and hit on the barrier placed near the road widening area and eventually ramped (sic) a Meralco post and ravine tree (sic).”

Two weeks later, a report released by a joint technical inspection team composed of the Tanay police, the National Bureau of Investigation, bus manufacturer Hino Motors Philippines and a road safety interest group found no mechanical problem with the brakes. The cause of the crash pointed to an error on the part of the driver, Julian Lacorda Jr., who was among those who died.

Former Land Transportation Office chief and now secretary-general of the Philippine Global Road Safety Partnership Alberto Suansing admits the joint technical inspection team could not make a detailed examination of all parts of the bus.

Suansing said that when the team arrived in Tanay on March 3, or 11 days after the crash, it found the wreckage of the bus at a covered court in Brgy. Sampaloc, already sawn off in two.

The Municipal Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office’s (MDRRMO) terminal report said Panda Coach Tours and Transport, the company that owned the bus, towed it the day after the crash with clearance from local police.

Spot the difference: Photo above shows how the Panda bus looked like after impact; below, how it looked like after it was cut in two and transferred. (Photo by Tanay MMDRMO and Verlie Q. Retulin)

“Here, you’ll see how the authorities handled, or mishandled, the evidence, maybe in their desire to clear the area,” said Suansing.

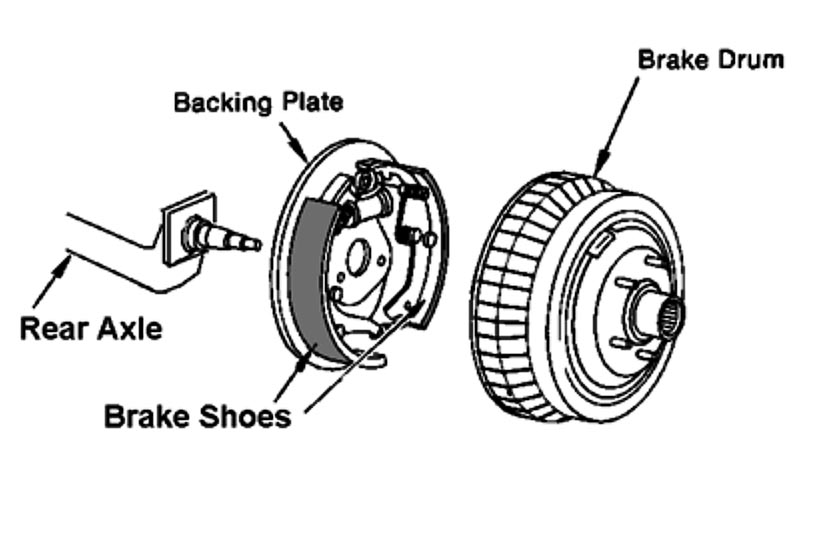

The team nevertheless focused on the bus’ brake system. Buses like Panda have a hydraulic brake system, which uses brake fluid to bring the wheels to a stop.

Once a driver steps on the foot valve or brake pedal of these buses, a plunger pushes the brake fluid from the master cylinder located near the engine through tubes called brake lines until the fluid reaches the braking unit of each wheel. There is a reservoir sitting above the master cylinder that supplies it with enough brake fluid.

Each of the four combination wheels of the Panda bus has a braking unit, as is common with buses.

The braking units are classified as drum brakes. Here, the brake fluid enters the wheel cylinder in each braking unit, which in turn pushes the brake shoe to attach itself to the brake drum. This will immobilize the wheel, bringing the vehicle to a stop.

Major parts of a typical drum brake. (Courtesy of www.carparts.com)

The team could only physically inspect the left rear brake of the bus. With all others, they had to make do with a visual inspection.

Based on their visual inspection, the team found no leaks on the wheel cylinders and the brake lines of the front and rear brakes. The reservoir still contained brake fluid, while the brake pedal was damaged, possibly when the collision happened, the report said.

For the left rear brake, which was the only accessible part of the bus according to Suansing, they took out the combination tires to expose the braking unit.

His group noticed the brake shoe was still thick, which means it wasn’t worn out, explained Suansing. “Mukhang bago pa nga (It even looks new),” he added. But around the lining was a white film called glazing, which indicates the brake shoe was subjected to intense heat due to friction.

The white line encircling the brake shoe is called “glazing,” which indicates it was subject to intense heat. (Photo courtesy of Alberto Suansing)

Suansing pointed out that the bus descent was long. “[The driver] was stepping on the pedal too often. That will heat up the brake shoe. When it glazes, it means it’s already hot,” he said. It’s the most likely source of the burning odor survivors reported smelling, he added.

More evidence of overheating was seen in the brake drum, based on the report: the inner part was blackened and showed heat cracks. The bearing grease was also melted. The group saw there was too much dirt and dust on both the brake shoe and brake drum surface.

There were no backing plates or dust covers which protect the braking unit from dirt. They concluded that this overheating “probably caused brake friction fade.”

Brake friction fade typically happens when there are sudden and sustained braking. This usually occurs when a driver “rides” the brake pedal while descending a mountainous terrain. The constant and abrupt stepping heats up the brake drums quickly, making them less responsive. This is why shifting to and driving in a lower gear, commonly known as doing an engine brake, is recommended when traversing this kind of landscape.

A jack is used to take out the left rear combination tires of the bus during inspection. (Photo courtesy of Alberto Suansing)

Suansing said they also found the gearshift in neutral, though this was not indicated in the group’s official report.

He speculates that the driver must have been driving in high gear and tried to downshift so he could use the engine brake to slow the bus down, but shifted to neutral instead. And then he got stuck there.

Because the bus was in neutral, it was therefore careening freely down the road, and the driver must have stepped on the brake pedal and stayed there the entire time, without shifting gear. “So he was freewheeling seconds before the impact, that’s why he came down fast,” Suansing said.

The group submitted their findings to the Tanay police on March 9. They said “there was no observed problem in the brake mechanical parts during the inspection.”

A veteran mechanic interviewed by VERA Files, however, said while the driver’s skills and behavior were questionable, the responsibility for the crash cannot be placed entirely on him.

The mechanic, who asked not to be named, agrees with the driver’s culpability, even saying Lacorda’s background should also have been thoroughly looked into. “Was he drugged or drunk the night before? How skilled was he as a driver?”

But he is adamant in saying it cannot be 100 percent the driver’s fault. If Panda maintained the bus properly, it could have helped in preventing the tragedy.

The joint technical inspection team’s findings seems to echoe Panda’s earlier statement that there was nothing wrong with the bus, which was inspected the day before the crash.

In a sworn statement, Panda auto mechanic Victor Imbat said he checked and adjusted the brakes and clutch lining of the bus on Feb. 19. He also conducted several maintenance procedures and spent six hours from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. working on the bus. This was their standard operating procedure before any trip, he said. He also said he went to the crash site after the incident to check on the bus’ brakes. He found nothing wrong with the brake system.

The veteran mechanic said this is inconsistent with the findings of Suansing’s technical inspection team. The mechanic, who owns an auto repair shop in Metro Manila, has been fixing and maintaining trucks, luxury vehicles and 4-wheel drives for more than two decades now. His clients include civil society organizations and local government units.

He said if Imbat indeed adjusted the brakes the day before, the brakes wouldn’t have been dirty, as found by the inspection team.

“Kung nag-adjust ka at binuksan mo, kasi naa-adjust iyan na ‘di mo binuksan, dapat wala ka nitong dumi. Ibig sabihin, hindi mo sinervice. Sinikwat mo lang na ina-adjust mo ( If you adjusted the brakes and opened them, because you can adjust without opening, there shouldn’t be this much dirt. So that means, you didn’t ‘service’ the bus. You just poked it),” he said.

The dirty brake shoe is scrutinized during the joint inspection team’s March 3 examination. (Photo courtesy of Alberto Suansing)

He said the proper way of checking and adjusting brakes especially during preventive maintenance would require all four combination wheels to be taken out to expose, inspect and clean the brakes.

“Bakit ka nagkaroon ng too much dirt? Kasi wala silang dash cover. Bakit naiipon (ang dumi)? Eh ‘di ang tagal na niyan, di mo binubuksan (Why did it have too much dirt? Because it had no dash cover. Why did dirt accumulate? Because you haven’t opened (the brakes) for a long time),” the mechanic said.

The report said the dirt found by the inspection team came from the environment and from worn out brake shoe material. Dirt enters the mechanism of the braking unit, causing wear and tear, which could contribute to the brake being prone to overheating.

Imbat also said he serviced the bus by himself for six hours.

The mechanic says the process of completing a proper check and adjustment on brakes alone in a bus like Panda would take at least 12 hours for a team of two. The difficulty of taking out the wheels and exposing the brake units alone takes time. And then Imbat had to clean each, unless he did not expose the brake units and just cleaned on the outside, which is the common practice among mechanics, he said.

The mechanic also noted that the brake shoe, though thick and seemingly in good condition, might actually be old or “expired.” Based on his experience, a brake shoe might be expired even if it is still thick.

An expired brake shoe hardens and may not react as quickly nor attach as firmly to the brake drum. It will also heat up faster. “When you buy an old vehicle, a traditional mechanic will say, the brake shoe’s still thick, we can still use it. You check the composition of the brake shoe, it looks okay and it works. But how old is it?” he says. It’s the drivers who usually sense when something is amiss with the brake shoe.

Suansing says poor maintenance is not a variable in this case and insists that it was a clear case of human error. “It was really the driver, the continuous pressing on the brake pedal which caused overheating.”

Former LTO Chairman Engr. Alberto Suansing

The Tanay police declared the crash “cased closed” on March 13.

“It was the driver’s error that ultimately led to the tragedy. The students said they smelled something burning and they told the driver. He should’ve stopped and checked the vehicle so the biggest fault is the driver’s,” said PO2 Joe Sevillena, the investigator assigned to the case.

The criminal liability of the suspect, the driver in this case, was the main point of the investigation conducted by the Tanay police, said Sevillena. The bus operators can still be held liable in a civil case, because vehicles should be roadworthy.

But that is no longer part of their work, he said.

The Panda bus was last examined at the LTO Motor Vehicle Inspection Center in Pasay in 2016. It passed the inspection.

But the Senate investigation into the Tanay bus crash has revealed that the country’s motor vehicle inspection system isn’t functioning well, despite the billions of pesos in motor vehicle users’ taxes that are channeled into it every year.

Land Transportation Office (LTO) Chief Edgar Galvante said during the Senate inquiry on the Tanay bus crash that the entire Motor Vehicle Inspection System (MVIS) in the country needs to be overhauled.

“The equipment we’re using for inspection do not function properly that’s why we rely on physical and visual inspection,” Galvante said. This applies to all nine Motor Vehicle Inspection Centers (MVIC) in the country.

This map shows the location of eight out of the nine MVICs in the country. These centers need to inspect millions of public utility vehicles yearly, and not all regions have an MVIC.

LTFRB chair Delgra echoed Galvante’s statement, explaining that because the government’s Motor Vehicle Inspection System (MVIS) is ineffective, transport agencies have had to place a 15-year-cap on the age of all buses and mini-buses for them to be considered roadworthy.

Suansing insists age does not determine a vehicle’s roadworthiness as laid down in government policies for the past two decades. “You have to test it. The vehicle has to undergo inspection. A respectable inspection system by the government needs to be in place,” he said.

Delgra agrees. He said a vehicle more than 15 years old can still be allowed to travel, if it were roadworthy. “Even if the bus is less than 15 years, if it’s not roadworthy, then we would not allow anymore the giving of franchise for such a unit,” he explains.

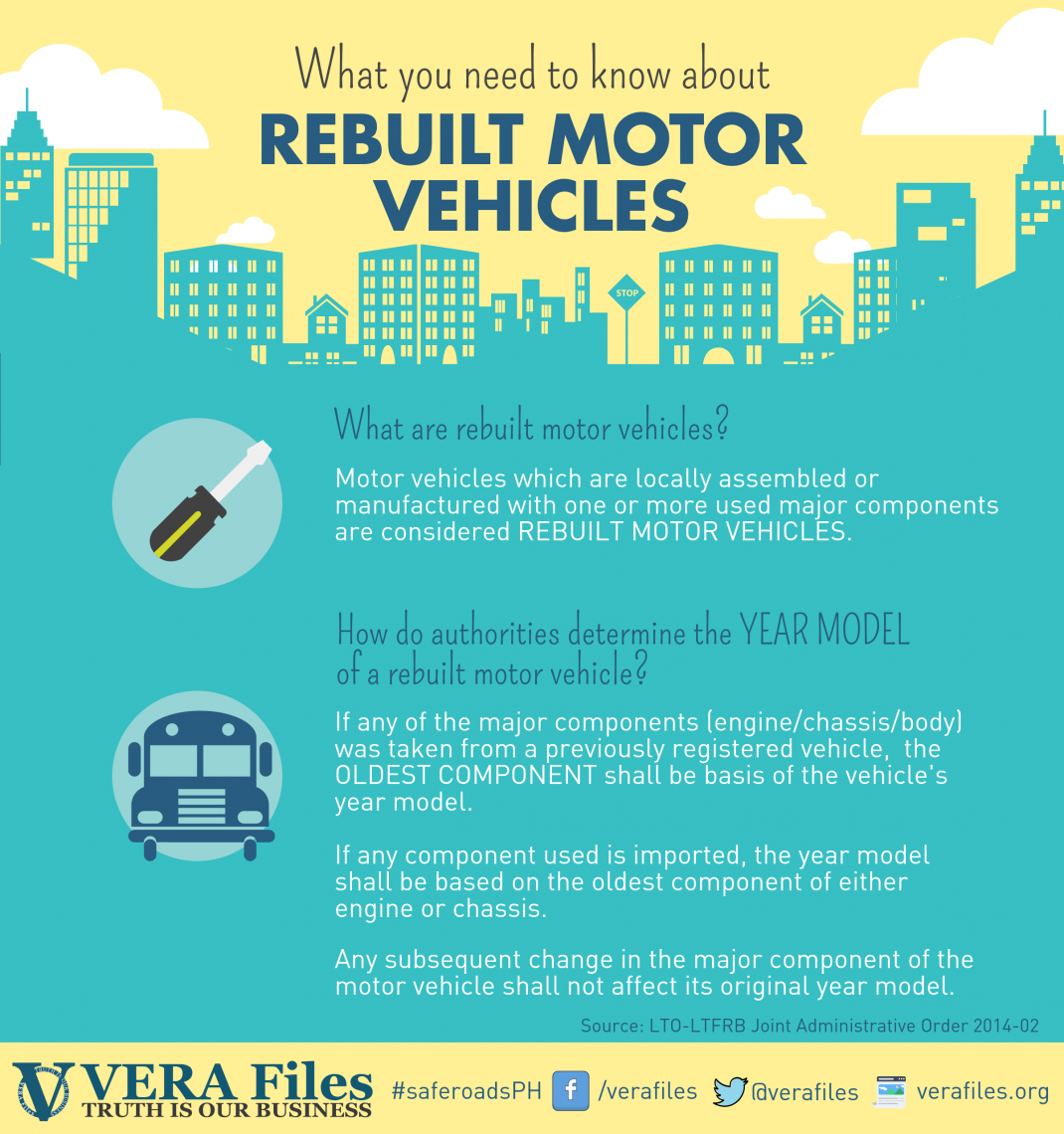

The age of the Panda bus became an issue when an LTFRB investigation found out the engine and the chassis or body did not match.

“Hino Japan confirmed that the engine number of that bus is of a different unit from the chassis number of the same bus. So at the time of the accident, the bus was a 29-year-old bus,” Delgra said, identifying the bus as similar to surplus units imported through Subic Freeport Zone.

The date of manufacture listed on the bus’ certificate of registration was 2004, even if Hino Motors in Japan built the bus in 1988, Delgra added.

The Land Transportation Office (LTO) is in charge of issuing certificates of registration for all vehicles in the country.

Based on the LTFRB’s 2013 memorandum setting a 15-year age limit for all buses and mini-buses in the country, the bus shouldn’t have been plying the roads in the first place, Delgra said.

Suansing pointed out there was nothing unlawful with the setup, as these are refurbished or rebuilt buses.

“There’s nothing anomalous as far as changing the engine is concerned. That was inspected in Subic and was declared roadworthy,” Suansing told the Senate committee.

Suansing told VERA Files that the likely explanation for the difference in the actual year model and the one recorded in LTO lies in the office’s policy.

In 2014, LTO and LTFRB came out with a joint administrative order (JAO), listing down guidelines in determining the year model of all vehicles. The goal was to identify the correct age of a vehicle to harmonize standards and properly implement the 15-year age limit.

In this JAO, the year model of rebuilt vehicles is based on the oldest major component of the bus – either the engine or the chassis.

But before 2014, LTO’s practice had been to record the year a bus was rebuilt and registered for the first time as its date of manufacture. Hence, the 2004 registration of the Panda bus with the 1988 chassis and new engine.

(To be concluded)

This story is produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, the Department of Transportation and VERA Files.