Melody, Rodolfo Daang’s favorite niece, looks at the wreck of the bike he was riding when he was killed in Noveleta, Cavite.

Sunday was always a special day for the Daangs, a working-class family who lives in Cavite.

The day before was salary day for Rodolfo Daang, and his nephews and nieces from his sister Rodilyn knew what it meant: their uncle would buy ice cream and donuts for all of them, bills would finally be paid and some groceries would be brought home. Melody, his favorite from the brood, would always anticipate her uncle’s return.

But Daang did not come that day, and, as they would later learn, would not be coming home again.

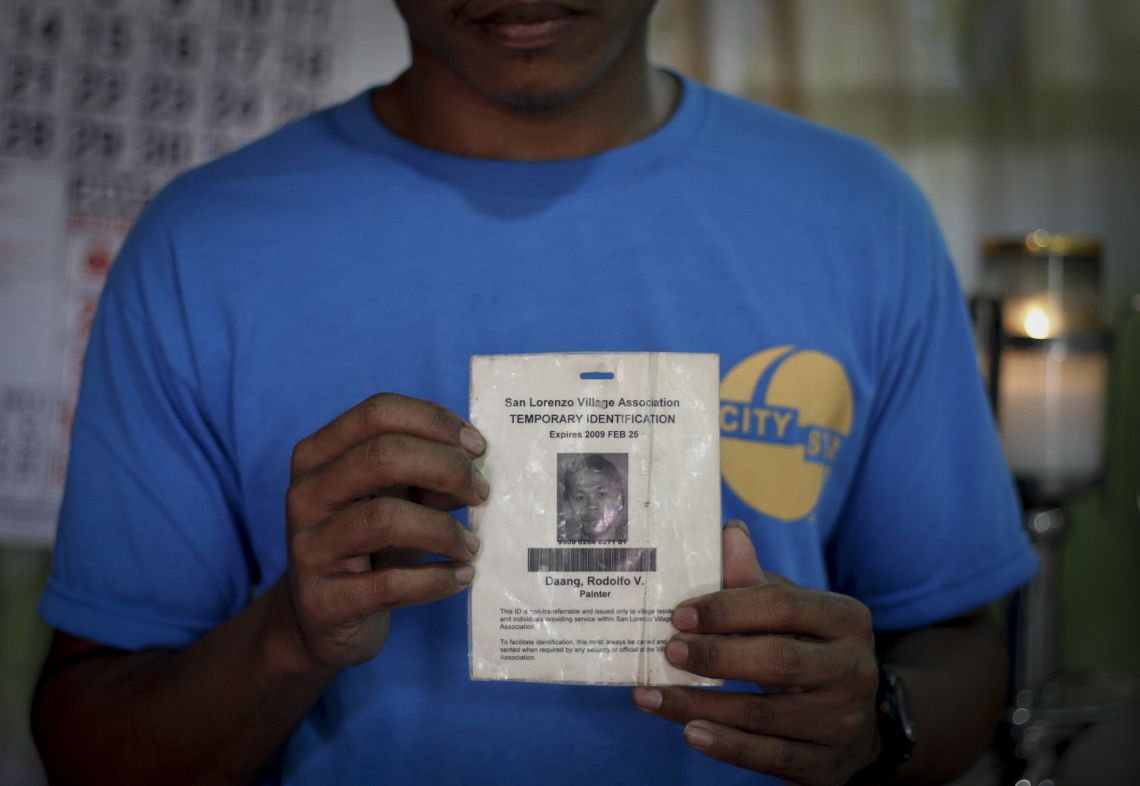

Rodolfo Daang’s younger brother shows his identification card.

At around 1 a.m. on April 30, while bicycling from work on the Noveleta Highway in Cavite, Daang was killed 3 kilometers away from his home when a speeding car overtook another car and rammed him.

He was 37 years old.

Daang was among a growing number of casualties due to road crashes. In 2016, 446 lost their lives Metro Manila because of it, according to a report by the Metro Manila Accident Recording and Analysis System (MMARAS).

In 2015 alone, the Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA) reported 26 deaths of bike riders due to road crashes. At least 926 people were also involved in bike-related crashes.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified bicyclists as one of the most vulnerable road users, together with pedestrians and motorcyclists. “Almost half of all deaths on world’s roads are among those with the least protection — motorcyclists, cyclists and pedestrians,” according to WHO’s Global Status Report on Road Safety 2015.

They are vulnerable because they lack protective shells, such as that of the encasement present in four-wheeled vehicles like cars and trucks. This causes them to suffer disproportionately in the event of collision, according to the Netherlands-based SWOV Institute for Road Safety Research.

While data on the number of bike users in the country are difficult to obtain, as the government does not require non-motorized vehicles to be registered with the Land Transportation Office, many low-income earners are known to use their bicycles for short-distance travel in an effort to save money on fares. Daang was one of them.

Daang was not originally from Cavite. A native of Tacloban, Leyte, he survived the destruction wreaked in the region by Typhoon Haiyan, one of the deadliest storms to ever hit the country. With hard work and the aid of foreign and local organizations, he was able to rebuild his small house and farm. He was able to go back to farming and tending to animals shortly.

When his brother-in-law had a mild stroke, he moved to Cavite to help his sister raise the couple’s three children. He found work as a contractual painter for a construction firm.

Daang’s safety hat and uniform, he clocked in a whole day’s work on a Saturday at a nearby construction site to augment the family’s income.

His brother-in-law used scrap metal and spare parts to make a bicycle which he would ride to Tagaytay, the site of a construction project where he worked, during weekdays. Often, he would even lend his bike to other construction workers who needed it.

In Barangay Salced Dos in Noveleta, where Daang lived with his family, most of the breadwinners are minimum wage workers who work in construction and factories.

“There are at least 20 workers in the village who use their bikes to work like me because we make savings that can be used to buy food,” Daang’s neighbor, Larry Ostos Vidal, said.

Vidal is a contractual heavy equipment operator and driver who works at the municipal government of Kawit in Cavite. He also rides a bike to work daily.

Vidal bikes an average of 8 kilometers everyday. “If I take public transport, I will pay P60 everyday, that’s why I ride my bike to work. I will save money,” he said.

With a daily minimum wage of P350, saving on fares is a priority for Vidal who has seven children, four of whom are still in school. Even a motorcycle would be too expensive for him; the maintenance and gas expenses would be too costly.

Biking meant saving 17 percent of his income for the day.

A study released in 2014 by the Japan International Cooperation Agency estimates that a typical Filipino family spends 20 percent of its income on transportation. The study predicts that by 2030, transportation costs will be 2.5 times higher, an additional burden to the commuting public already saddled by safety concerns and daily hours-long gridlocks on the road.

The daily minimum wage in the NCR is pegged at P491, according to a 2016 yearend study published by think tank IBON Foundation. However, the real value of these wages have eroded by 2.7 percent due to inflation in 2015 and 2016, the study said.

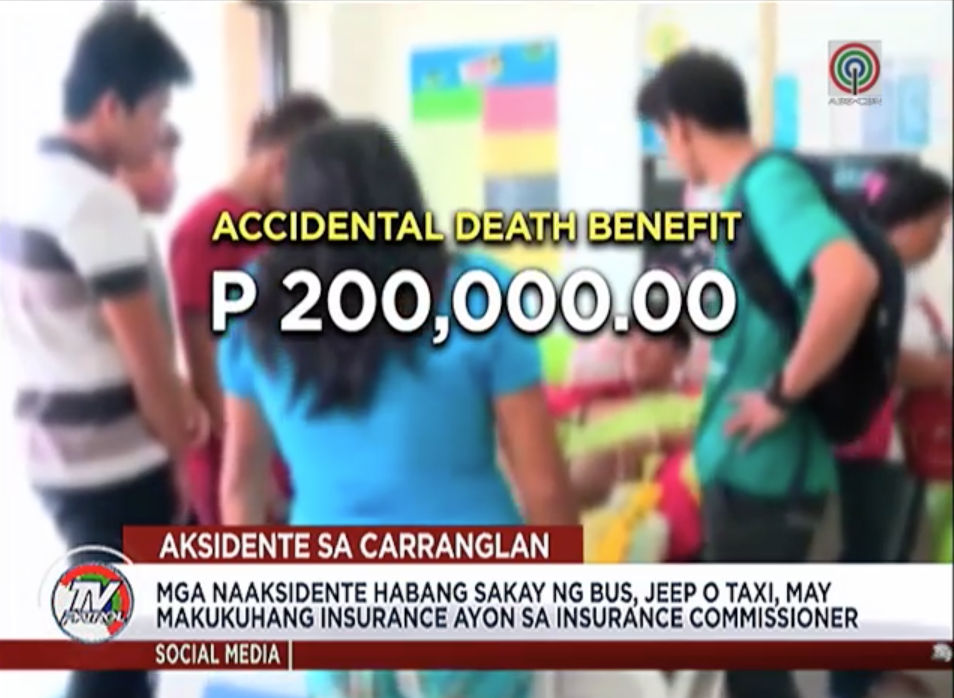

The death of a family member from a road crash means more financial hardships to a household, particularly those coming from low-income sections of society. “In low and middle income countries, [road crashes] they particularly affect the economically active age group, or those set to contribute to family, society and the workforce in general,” according to WHO.

Deaths and injuries resulting from road crashes can also place economic burden on the national economy, health and legal systems. It is estimated that road traffic deaths and injuries can cost low and middle-income countries as much as 5 percent of the country’s GDP, WHO says.

Despite the need to ensure the safety of those who regularly use their bikes as a mode of transportation, the current road infrastructure in the country does not support bike riders.

In Metro Manila, only a handful of cities have implemented segregated bike lanes.

Marikina City opened 100 kilometers of bike lanes in 2000. In a Metro Manila Urban Transportation Integration Study (MMUTIS) report published in 2014, it is said that around 10,500 daily trips are made in Marikina City by bicycle. This accounts for 6.5 percent of bicycle trips made in Metro Manila in 1996.

The Marikina Bikeways System was implemented to encourage citizens to use a more environmentally friendly mode of transportation and benefit those from lower-income segments.

While Marikina City is hailed as a model for integrating bikeways into existing roads, road crashes involving bike riders are still commonplace.

The government has plans for bikers. The Philippine Road Safety Action Plan, a comprehensive, multi-agency transportation plan led by the Department of Transportation, wants to integrate road safety facilities for vulnerable road users and persons with disabilities in the design of existing and new roads.

C6, a 34-kilometer toll road from Taguig to the Batasan Complex in Quezon City, will incorporate a bike way, MMDA assistant general manager Julia Nebrija said.

In the meantime however, cyclists who share the road with motorized vehicles must contend with the daily risk of getting killed on the road, especially in the face of competition for space.

In Daang’s family, his death meant loss of income for the whole household, since Rodilyn’s husband, the other breadwinner, has not found a steady job and is still recovering from stroke.

Rodilyn and her daughter Melody sit beside the casket of her brother Rodolfo Daang, a contractual painter who was killed while biking along Noveleta Highway in Cavite.

“My brother had big dreams for my children. He said he wanted his nephews and nieces to finish school so that they can find better jobs. I don’t know how we will do that now,” she said.

They have not been able to find the owner of the car that killed Daang. Rodilyn said that police officers assigned to her brother’s case have not been responding to their inquiries via text messages.

Daang’s family also had to scrape together P10,000 to pay for his funeral expenses.

Rodilyn said she had to ask her relatives in the province to sell Rodolfo’s pig, which he had bought using the financial aid he received from NGOs as a Typhoon Haiyan survivor. Her neighbors also pitched in whatever amount they could give to help the family cover the costs of the burial.

Daang’s body was finally laid to rest on May 14, nearly two weeks after his death.

Despite unresponsive local police, Rodilyn remains hopeful that justice will be served. She is still hoping that a witness will come forward to identify his brother’s killer.

She recalls that her brother, a deeply compassionate and forgiving man, would only request for an apology in the face of the gravest mistake committed against him.

“[The driver] can at least apologize to us. If we will not find him, how many more will be killed? Just because we are poor and cannot afford to press charges doesn’t mean we do not deserve justice,” Rodilyn said.

This story, first published on Interaksyon, was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.