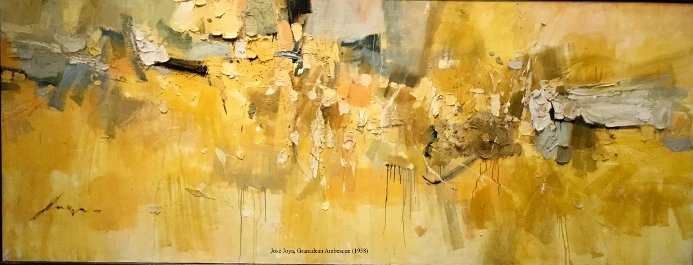

Jose Joya’s Granadean Arabesque (1958)

The brightest color that the human eye can see, yellow is color

between orange and green in the visible light spectrum. Associated

with sunshine and brightness, as well as happiness and optimism, it

is the color of ripeness in bananas and mangoes, of the Beatles’

Yellow Submarine, the “smiley” face emoji, or Van Gogh’s

starry nights and sunflowers. And it is the color of graduation time

in UP Diliman’s rows of blooming sunflowers.

Yellow Ambiguities celebrates the color yellow in all its hues and

shades at the Ateneo Art Gallery, Areté, Ateneo de Manila University

until 05 January 2020.

Jose Joya’s Granadean Arabesque (1958) immediately greets the viewers

and sets the tone of the exhibit, with its thick broad strokes of

impasto and sand in celebration of tropical radiance.

Mellow yellow complexity

Various woven textiles

With some 90 artworks on display, the exhibition explores the

complexity of yellow as seen in “its materials, culture, art

history, and concept.” Divided into five sections — Forms and

Ideas, Tropics and Heat, Illness and Struggle, Halos and

Illuminations, and Properties and Surfaces — the exhibit presents

how yellow is used in a variety of media such as plastic vines,

feathers, collage, pencils, archival pigment print, photographs, gold

ornaments and hand-woven textiles, and an assemblage that refers to

that “little patch of yellow” in Vermeer’s painting,

View

of Delft

.

The heat is on

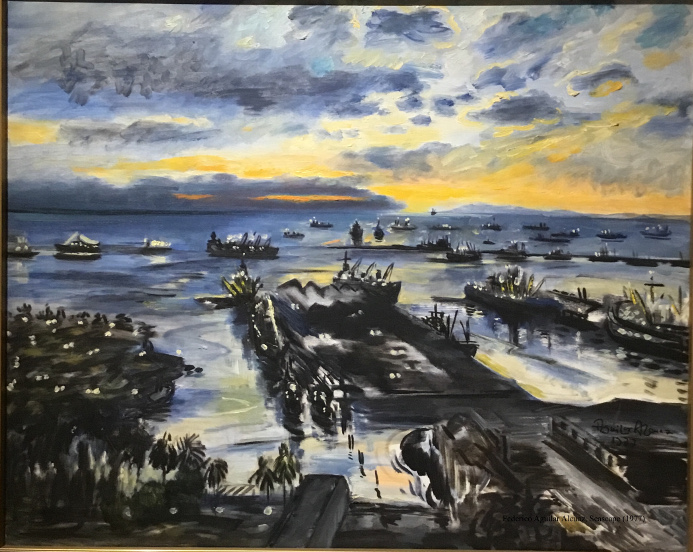

Federico Aguilar Alcuaz, Seascape (1977)

In the section Tropics and Heat, life in tropical intensity starts

with Federico Aguilar Alcuaz,

Seascape (1977) in black and deep blues

with dawn breaking in yellow streaks of sunlight. The idylls of rural

life, so romanticized, leads us to Diosdado Lorenzo’s

The Farmer’s

House

(1958) or even Amorsolo’s Preparing a Noon Day Meal Under a

Mango Tree

(1941). Eating on the go in the filthy streets of Manila

is seen in Daniel Coquilla’s

AristoCart (1995), amidst signs and

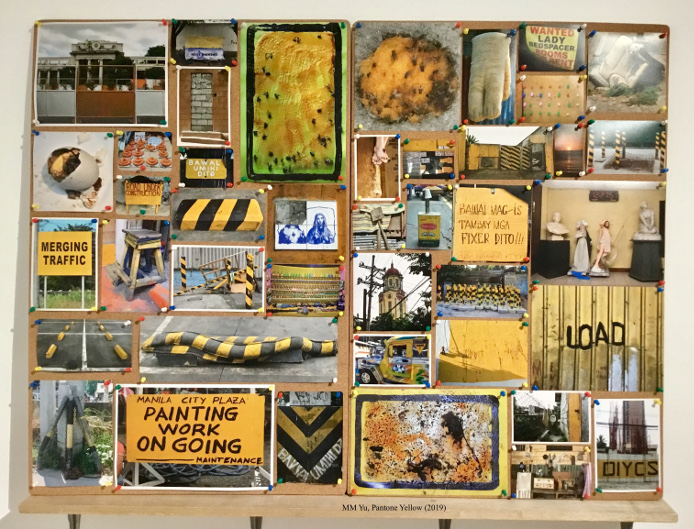

symbols in MM Yu’s

Pantone Yellow (2019) and the presence of

mom-and-pop stores everywhere by Antonio Austria,

Sari-Sari Store

(1965). Urban heat and humidity accelerates in Jeepneys (1951) by

Vicente Manansala. Life in the city ends with a night of drunken

stupor in

Last Order (1994) by Jeho Bitancor. The tropical spell is

broken with Edgar Talusan Fernandez,

The Year to Remember (1983), a

thick yellow blanket crumpled on the ground with yellow ribbons

hanging over it, a reference to the Aquino assassination in 1983,

still unsolved to this day. In recent times, Manny Montelibano’s

Uncertainty at the Beach -Temperature (2018), a video installation

looped with Duterte’s rambling speech punctured with profanities. It

forms a grating soundscape, in contrast to Areté’s quietness.

MM Yu’s Pantone Yellow (2019)

Edgar Talusan Fernandez, The Year to Remember (1983)

Natural sources

Abundant in the natural world, minerals and botanical plants are the

source of natural dyes and pigments for yellow. As such, it suggests

blossoming and ripeness; also of pallor and decay. Yellow ochre (and

red) from clay is one of the earliest pigments used in art; the

Lascaux Caves in France is full of Paleolithic paintings of large

animals such as bisons, bulls, and horses painted in yellow,

estimated to be 20,000 years old.

In the Philippines, pre-Spanish gold ornaments had been used as part

of an ancient burial practice. It is believed that gold death mask

prevents the entry of evil spirits. Such masks have been excavated in

Oton, Iloilo and Butuan, Agusan del Norte where gold was once

abundant.

Yellow is also reflected in the traditional colors of woven fabrics,

dyed with turmeric and lemongrass, such as Mangyan and Itneg textiles

or the Maranao malong included in the exhibition, reflecting the

country’s rich culture of weaving.

Divine light

Ang Kiukok’s Madonna-Santo Rosario (1983)

Halos and illuminations in yellow have been used to depict gods,

saints, and divine beings to separate them from mere mortals. The

exhibit explores how the color yellow is reflected in the country’s

religious culture during the Spanish colonial period and how

contemporary artists incorporate such narrative and history into

their works.

Evoking light and vibrancy, Galo B. Ocampo’s Brown Madonna (1938) and

Ang Kiukok’s

Madonna-Santo Rosario (1983) carry the luminosity of

yellow in full force; Edgar Talusan Fernandez’

Sining Kalayaan

(1987/1997) places a yellow orb behind the nation as Mother Freedom

in a battle between evil vs. good. And Anton del Castillo’s

State of

Nothingness

(2006), oil on gold leaf panel resembling Byzantine

icons, pays homage to ordinary Filipinos.

Beyond yellow ‘s association in the country’s political history, and

its recent denigration to “dilawan” (as synonymous to

those who espouse critical thinking or liberalism), the exhibition

forces us to rethink and reframe the color yellow for what is —

light and life — the source of vital energy encapsulated in the sun

rising for another new dawn.