VERA Files is 10 years old.

To mark our 10th anniversary, we are reposting 10 stories that mirror the group’s interest and commitments.

Here is the second of a three-part special report published September 2008, which won the top prize in the 20th Jaime V. Ongpin Awards for Excellence in Journalism in 2009 organized by the Center for Media Freedom and Responsibility. It shared the top honors with Roel Landingin’s three-part series on official development assistance for the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism.

One of the writers, Diosa Labiste, was awarded the Marshall McLuhan Prize by the Canadian Embassy.

MANILA, Philippines — The Quedan and Rural Credit Guarantee Corp. (Quedancor) does not only give out loans to the poor. It also “lends” money to “needy” politicians, congressmen included.

Insiders say Quedancor is the one government corporation politicians know they can run to when they want cash—for political reasons or otherwise. The “loans” are known within Quedancor as “political accounts.”

Officially, these “political accounts” do not exist; there is no record of them in Quedancor’s books. A Quedancor official said these are either hidden in Quedancor’s local government account or distributed across various programs.

These “political accounts” have partly contributed to the huge past due receivables—nearly P4 billion—that Quedancor is saddled with. Metro Manila accounts for P745 million and Region 13 (Caraga), P636 million.

At first, it was easy holding politicians accountable since a number of these loans were actually documented. That was in the few years after 1992 when Congress passed the law turning Quedancor into a state corporation.

For example, the Agricultural Credit Policy Council, an agency attached to the Department of Agriculture, loaned about P20 million to Quedancor in 1993 and 1994. The money went to a micro-credit program that was among the congressional initiative allocations—pork barrel projects—of Quirino Rep. Junie Cua. A decade later in 2004, P15.4 million of that loan was still unpaid and had to be restructured. Cua is now chair of the House appropriations committee.

Nowadays, politicians no longer leave a paper trail at Quedancor, thanks to a four-member “Special Operations” Group, which is Quedancor’s “one-stop shop” for congressmen, governors and mayors.

This group has existed since the late 1990s and takes orders from a Quedancor executive who transacts directly with politicians, especially those allied with the administration, a Quedancor official privy to the group’s operations said. The group includes a Quedancor district supervisor and an assistant vice president.

The group goes through the motions of processing loans. It supposedly conducts credit investigations, but in reality, it lines up “ghost” borrowers in whose names the “political accounts” will be given. The group also manufactures or overappraises collaterals in exchange for 15- to 20-percent “commission,” the official said.

Quedancor’s poor accounting system makes it difficult to trace the funds. An internal audit found no clear trail of fund transfers from the Quedancor central office in Quezon City to its field offices, which rarely monitor remittances and often submit financial reports information late.

In 2001, Quedancor undertook a program that four Quedancor officials, in separate interviews, said was tantamout to yet another “political account”: the Urban and Rural Poor Program or URP.

Launched in Pangasinan months after Gloria Arroyo assumed the presidency, the URP was designed to win over the poor, including those in the urban areas. The idea came after the May 1 rally in which the urban poor marched to Malacañang in an attempt to unseat her shaky government. “We didn’t have an urban poor project until then,” said one of the officials.

On June 6, 2002, about 2,000 residents of Barangay Holy Spirit in Quezon City, mostly market retailers and ambulant entrepreneurs like taho and balut vendors, received loans totaling nearly P15 million, with Arroyo herself handing out the checks. A week later P10 million was released to Caloocan City residents.

“Bumuhos ang pera; doleout talaga (Money flowed; it was really doleout),” the official said.

On some occasions, individual checks, averaging P10,000, were released even before vouchers were signed, another official said. The vouchers would be fixed afterwards.

In the program’s early years, all the departments at Quedancor were sent out to conduct credit investigations. “Tumigil ang mundo ng Quedancor noon. May nag-utos sa taas (Everything stopped at Quedancor at that time. The order came from above),” the official said.

The official said many of them found the task ridiculous: “What credit investigation can you do on an ambulant vendor? How do you monitor urban gardening?”

To this day, the URP records the lowest repayment rate and fewest accomplishments, and is characterized by incomplete or nonexistent paperwork. Yet more than P1 billion has been poured into the program. This includes at least P110 million from the controversial P5-billion loan released by Equitable PCIBank and Land Bank to Quedancor before the 2004 elections.

The P110 million accounts for one-third of the P393 million released to the URP, the biggest sum ever released in the seven-year program.

Of the P393 million, one-third or P135 million went to Region 13 (Caraga) where Quedancor president-on-leave Nelson Buenaflor hails from. Buenaflor is from Tandag, Surigao del Sur. Region 9 (Western Mindanao) and Region 7 (Central Visayas) also received big amounts. These are areas where Arroyo posted big wins in the 2004 elections.

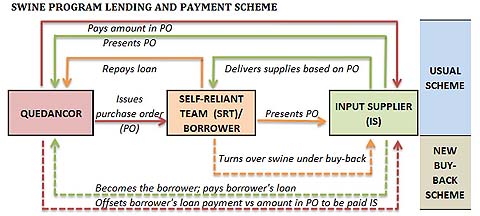

In a book titled Quedancor: The Country’s Premiere Credit and Guarantee Company, Quedancor executives wrote that the URP “precipitated” what would later be touted as an innovative no-collateral lending scheme for micro-borrowers: The Self-Reliant Team (SRT) Model. In fact, Buenaflor likes to be called the “Father of the SRT.”

An SRT consists of three to 15 members who live in the same barangay, have the same project and act as co-guarantors. The SRT issues postdated checks to Quedancor as payment for a three-year loan of up to P50,000 for a production projects and P20,000 for a livelihood project.

The projects range from grains and high-value crops, to fisheries, livestock and poultry, and other commodities, including swine-raising and the URP. A production loan bears a yearly interest of 14 percent and working capital loan, a monthly 2 percent.

Quedancor claims that half a million beneficiaries availed themselves of the billions of pesos released as SRT loans, including those funded by the Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Competitiveness Enhancement Fund. It also claims a 98-percent repayment rate.

But the SRTs appear to be going the way of the Quedancor Swine Program. Some borrowers are already defaulting on their loans, after they organized themselves into municipal cooperatives or agri-fishery business organizations (AFBOs) in 2005 to qualify for the bigger loans that ran into millions of pesos.

It turns out that some of these SRT-AFBOs had Quedancor officials and employees themselves as members.

When 2006 ended, these SRT-AFBOs owed the government P380 million, which the Commission on Audit says run a “high risk of credit default.” The loans were released to cooperatives, mostly in Mindanao. Caraga got P212 million or more than half the amount.

“Most of the SRT-AFBO loan applications were processed in haste and were approved despite the borrowers’ noncompliance with the guidelines,” COA said, hinting that Quedancor appears to have “construed its mandate simply as doleout of government funds (and) disregarded its recovery.”

Formed only in 2005, all the cooperatives could not meet the required two-year track record of lending activity. But Quedancor still released loans to many less than a month after they registered with the Cooperative Development Authority (CDA). Quedancor also granted many loans to AFBOs that lacked the required capital, net worth, collateral and security documents.

The cooperative in Digos, Davao del Sur, for example, got its first loan of P4.5 million from Quedancor on Dec. 14, 2005, less than a month after registering with the CDA. Its paidup capital was only P48,000. Yet by October 2006, it had received P16.2 million in loans.

Several cooperatives like those in Koronadal and Norala in South Cotabato had received loans even before they registered with the CDA.

COA also said it was unsure if the cooperatives ever released loans to their members because there was no money trail.

Already, COA has come across a number of SRT-AFBOs defaulting on their loans. Repayment is a low 2 to 5 percent for many cooperatives.

“The problem with the SRTs is they were prematurely converted to cooperatives or AFBOs. The loans reached millions where it used to be just P20,000. Nasira ang credit discipline (The credit disipline was ruined),” said a Quedancor executive.

COA has called Quedancor’s attention to what it suspects to be the involvement of its officials and employees in flouting the corporation’s guidelines on the SRT-AFBOs.

An internal audit said the SRT-AFBOs, a private entity, were practically established and financed by Quedancor. Quedancor organized and paid for the training of cooperative officers and personnel, including a seminar in Camelot Hotel in Quezon City in 2005, it said.

The internal audit also found that some Quedancor district officers, particularly in Caraga, even hired and paid emergency employees and later assigned them to the cooperatives.

In all, Quedancor issued 17 memoranda related to the SRT-AFBOs between June 14, 2005 and June 20, 2006. A number of these were apparently designed to enable the cooperatives to skirt Quedancor’s loan requirements, according to internal auditors and COA.

Because all the newly established cooperatives could not comply with the required two-year track record, Quedancor issued Memorandum 196 removing this requirement, as well the security arrangements for the issuance of postdated checks.

Memorandum 123, meanwhile, authorized the regional assistant vice presidents to approve all loans of the SRT-AFBOs, regardless of the amount. Previously, the regional executives could approve loans of up to P1 million only.

COA said the issuance of Memo 123 raises a big question: Why was the authorized loan limit removed? Without the limit, the loan privilege was opened to abuse and the working capital easily depleted.

Without monitoring and accounting, the decentralization of Quedancor’s authority became, in the words of another Quedancor official, “a grand scheme of robbing the organization.”

Both COA and internal auditors point to what constitutes conflicts of interests on the part of several Quedancor officials, including Buenaflor, who had a hand in getting the cooperatives to form the SRT Philippines Federation of Municipal Agri-Fishery Multipurpose Cooperative (SRT Philippines) and the Kaisa sa Mabuting Gawa Foundation (Kaisa). The two organizations were registered on Dec. 27, 2005.

Organized by 52 cooperatives, 36 of them Mindanao-based, SRT Philippines is headed by Nelson Bughao, Quedancor’s former regional assistant vice president in Caraga and Buenaflor’s townmate.

Its certificate of registration with the CDA lists Quedancor’s address at 34 Panay Avenue, Quezon City, and Buenaflor as honorary chairman. “He will be lifetime honorary chairman of the federation unless appointed and/or elected for an official function or position if eligible or qualified,” the certificate reads.

The federation has an authorized capital stock of P200 million, of which P50 million has been subscribed and P15.9 million paid up.

Kaisa, on the other hand, was organized by Buenaflor and Quedancor vice presidents Delano Anover Jr., Alberto Guevarra, Rodelio Bathan and Armando Crobalde Jr., chief of staff Edelyn Cadapan, and Cherrelyn Barrameda, then a staff member at Buenaflor’s office.

Its registration papers with the Securities and Exchange Commission list Buenaflor’s home address as its address and show a P1.54-million capital, mostly from members’ contributions.

COA and internal auditors found a November 2005 memorandum signed by senior vice president Niels Patrick C. Riconalla that required, “without legal basis,” the SRT-AFBOs to each pay SRT Philippines P500,000 as capital buildup and contribute P25,000 to Kaisa.

Another memorandum issued the same month required Quedancor borrowers to become members of the cooperatives and compulsorily deducted from each of them P200 for membership fee and at least P2,500 for the capital buildup. The memo was later amended to make membership in SRT cooperatives optional.

“SRT-AFBOs or cooperatives are private entities; thus, Quedancor has no legal personality to collect (capital buildup) and membership fees for and in behalf of these private cooperatives,” the internal auditors said.

Many cooperatives complied with the Quedancor directive, remitting the specified sums to SRT Philippines and the federation in checks that were mostly “paid to cash,” COA and the internal audit found.

“Since all the SRT municipal cooperatives were established and financed by Quendancor through deductions of (capital buildup) from Quedancor borrowers, obviously the funds paid by the municipal cooperatives of the SRT Federation are funds that came from Quedancor,” the internal auditors concluded.

Buenaflor has been charged before the Office of the Ombudsman for his alleged involvement in the anomalous swine and SRT-AFBO programs.

Part 1: Quedancor Swine Program another fertilizer scam