Two young Filipinas had a tie that bound them. They were both victims of rape by their kin in their innocence.It was with sheer wonder and fascination that they embarked together on a research journey — validating a finding from an anthropological study of the Bontoks, where no one knew about rape.

Last month, in celebration of Women’s Month, the Film Development Council of the Philippines (FDCP) and Gabriela Network of Professionals (GNET) held special screenings of the multi-awarded documentary, “Walang rape sa Bontok,” one hour and 58 minutes of rich, informative details of the traditional culture and practices of Bontoc, the crossroad to the Cordillera Region, and affirming that indeed, rape did not exist in this slice of heaven, at least for a very long period, before militarization crept in. There was no word for it, no concept and no punishment for such a crime that did not exist in Bontoc haven.

The two filmmakers who make up the Habi Collective, Lester Valle and Carla Samantha Ocampo, together with research assistant Annalaine Denise Magas, produced and wrote this film in 2014 as its entry to the GMA TV News Network’s invite for documentaries, and was a participant in the Cine Totoo Festival, shown for two weeks at the SM Malls.

The germ of the idea for the story was plucked from their deep study of the renowned anthropologist June Prill-Brett’s research on the Bontoc’s ways and mores, ”Gender Relations in Bontok Society.” The filmmakers endeavored to find out through immersion and many oral interviews with the elders and the academics in the Cordilleras why such a rapeless situation did thrive in this society. Dr. Brett’s study validated that men and women are of equal importance in Bontoc society.

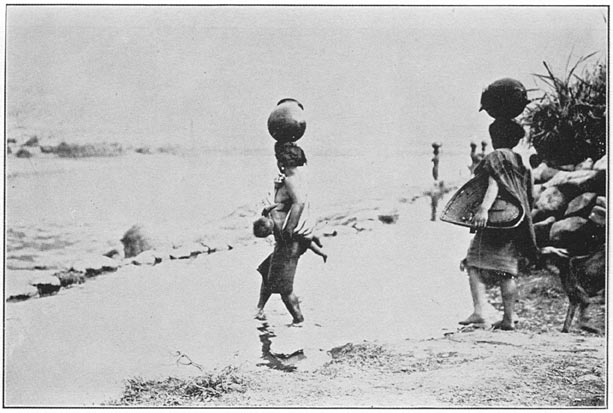

The film showed how the Bontoc women were barechested almost all their lives, even in public places, even when they walked to the market hoisting a basketful of camote on top of their heads. No jeers, no disrespect come from anyone in the community. For them breasts did not elicit anything sexual. Breasts were sources of milk and nourishment for their children. No naughty fantasies exist in their minds.

Bontoc women are those who plant rice seedlings in the fields, as well as seeds of any other fruit.It is their belief that when the men do the planting, the yields are not that bountiful.

In social events like wedding feasts, only women can serve rice to the guests. It is a role with distinction.

In case of inter-village wars, no rape can ever occur, because when the enemy forces approach the women of the rival village, all that a woman has to do is to raise her skirt and show her genitals, and the enemy will scamper away, because in their culture this is a bad omen, and synonymous with death. Their notion is that no man can look at a woman’s genitalia, that being the channel from whence he came into the world.

The academics also point out how extremely difficult life is, in these parts. They toil all day in the fields (the land here not being too fertile), and so when they go back to their dwellings, both husband and wife are so bone tired that they just have to sleep off their aching bodies.

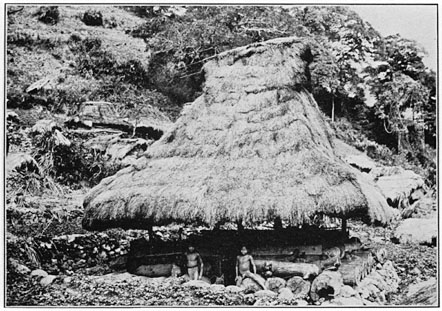

At the turn of puberty, sisters and brothers are made to sleep separately, the girls in the ologs, accommodating about eight lasses at a time.The atos are the sleeping quarters for the males, and these can accommodate around 20 to 30 of them. Strict rules and discipline are imposed in these sleeping cottages, so that no malice or hanky panky can happen.

When a man commits a crime in this society, there is no forgiveness. He is ostracized forever.If he attends gatherings, he is assigned to a space at the rearmost and his food and drink are given him, but in the rudest and unwelcoming manner.

In the open forum that followed the screening, Carla Ocampo, the film’s scriptwriter and a professor of film at the College of Saint Benilde, said she hopes that the filming of documentaries should be encouraged, especially among women talents, as this is a unique form of assertiveness coming from women.“There is a quiet power behind the camera,” she said.

Political writer Sharon Cabusao said,” It is a liberating film, using a socio-anthropological lens.”Bibeth Orteza Siguion Reyna, actress , writer and activist dreams further by envisioning works of literature , such as Florante at Laura, to be made into teleseryes, “since admittedly, a lot of Filipinos do not read anymore.”

As an aside, Philippine Star Lifestyle writer Irish Dizon narrated how empowered she became after watching Heneral Luna.It opened her eyes to the need to become nationalistic and she said, it was because of this film that she made up her mind to register herself as a Comelec voter.

“Walang Rape sa Bontok” won the Gawad Urian award for documentaries in 2014 and also was a big hit in New York when it participated in the New York Festival of the World’s Best TV and Films Competition for the Documentary Category.