The issue of President Rodrigo Duterte’s health was on the front pages again when he failed to show up in a barangay summit on peace and order in Palo, Leyte on Feb. 1 because he was “not feeling well,” according to the president’s former aide and now senatorial candidate Christopher “Bong” Go.

Instead of an official statement from Malacañang on the president’s condition, Duterte’s partner Honeylet Avanceña posted on Facebook a series of videos of the president, mocking rumors about his “death.”

“For those who believe in the news that I passed away, then I request of you, please pray for the eternal repose of my soul. Thank you,” he said in the video.

Duterte’s macabre sense of humor does not address the concern of majority of Filipinos worried about the president’s health.

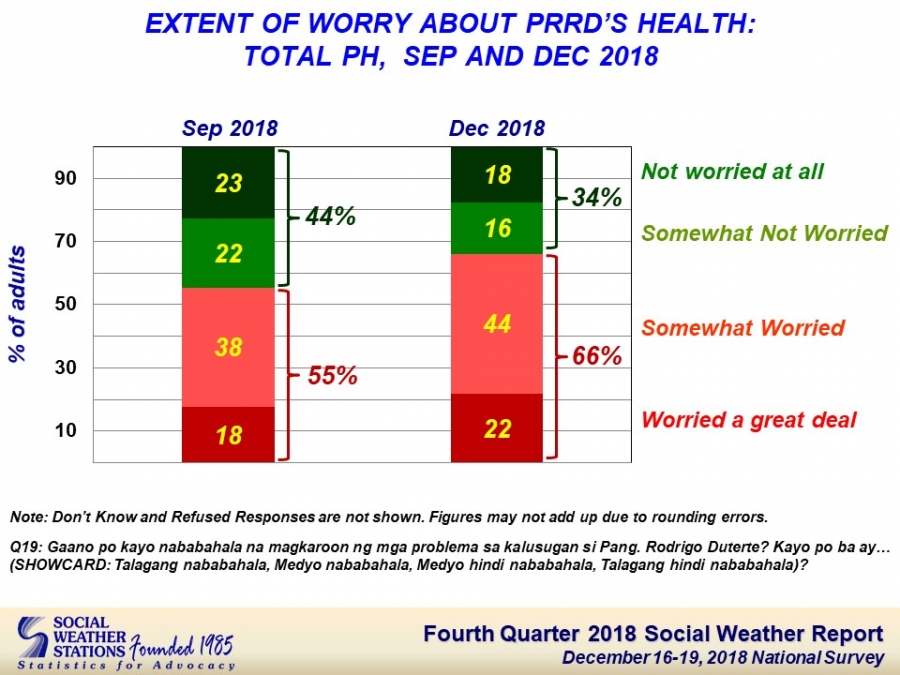

The Social Weather Stations’ 2018 fourth quarter survey released last month showed that 66 percent of adult Filipinos are “worried” about Duterte’s health, showing an increase from the previous quarter’s 55 percent.

An SWS graph of the results of its “Extent of Worry on PRRD’s health” survey conducted in December 2018

Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo spinned this to Duterte’s favor saying “not only many Filipinos love the President but those who care for him have increased by 11 percent.”

The SWS survey also found that 49 percent of adult Filipinos believe Duterte currently has health problems.

But despite the increase in the number of Filipinos who “care” about Duterte’s health, definitive information on the matter remains elusive, even with this administration’s Freedom of Information (FOI) directive.

Sec. 12, Art. 7 of the Constitution requires the public be informed of the president’s state of health in case of “serious illness.”

Prompted by Duterte’s pronouncements in October 2018 that he underwent medical tests amid rumors of his deteriorating condition, VERA Files filed an FOI request with the Office of the President (OP) to get the real score on the president’s health.

The request was eventually denied after a process riddled with technicalities and vague explanations.

Hospital visit

On Oct. 3, 2018, information made rounds on social media that the president was seen at the Cardinal Santos Medical Center in San Juan City very early in the morning.

It set reporters and the public alike in a frenzy as only weeks before communist leader Jose Maria Sison, based in the Netherlands, claimed that he received information that Duterte was seriously ill or even went into a coma.

Former presidential spokesperson Harry Roque speaks to the press on Oct. 5, 2018

Then presidential spokesperson Harry Roque firmly denied the hospital visit, only to be discredited the next day by Duterte himself when he admitted in a speech that he did go to the hospital for a check-up. He disclosed that weeks earlier he had undergone an endoscopy, a nonsurgical procedure used to examine the digestive track, and a colonoscopy, an examination of the large intestines for any abnormalities.

Pressed for the result of his medical tests during a media briefing a week later, Duterte said he was “not yet cancerous” and that he merely had a bad case of Barrett’s disease, an inflammation in the esophagus, from drinking too much.

Malacañang did not issue a medical bulletin or release Duterte’s medical records, maintaining his condition was “not serious,” as required under the Constitution for records to be made public.

On Oct. 12, 2018, VERA Files filed an FOI request via email. It read:

“In light of the President’s recent medical tests, unofficial pronouncements by some members of his Cabinet pertaining to his health, and in line with the provisions of the Executive Order No. 2 on the people’s right to information on matters involving public interest, we would like to request for an official statement or records on the medical condition of President Duterte.”

It was received by the Malacañang Records Office (MRO), the OP’s designated receiving office for FOI matters.

A screenshot of the MRO’s acknowledgement of VERA Files’ FOI request.

File ‘not in possession’

The OP’s FOI manual mandates each request be addressed within 15 working days, during which time the MRO shall redirect the request to the appropriate FOI evaluating office (FEO), or the division that holds the sought information. This office will then address the request.

In case it is unclear which office holds custody of the requested information, the MRO shall be the default FEO, the manual said.

After the 15-day wait, VERA Files got its response: Denied. The MRO said in an email:

“Please be informed that the information requested is not among the records available on file nor in the possession of this Office. Hence it is unable to provide the sought information. We shall gladly accommodate your request once the requested information becomes available for release.”

It was not clear from the email which department acted as the FEO in the request. VERA Files sent a reply on Nov. 12 to clarify, but got no response.

Instead, the MRO told VERA Files in a follow-up phone call to file a separate FOI request addressed to MRO Director IV Concepcion Ferrolino-Enad for further questions to be accommodated.

VERA Files filed its second FOI request on Nov. 14, again, through email to clarify which division under the OP served as the evaluating office on Duterte’s health matters.

The MRO responded the next day, “kindly requesting” VERA Files to resend the request using the FOI form, along with two valid government IDs, as stated in the manual. These requirements were were not sought in the original FOI request.

VERA Files sent the revised request complete with the form and IDs on the same day, Nov. 15; it was acknowledged on Nov. 19, two working days later.

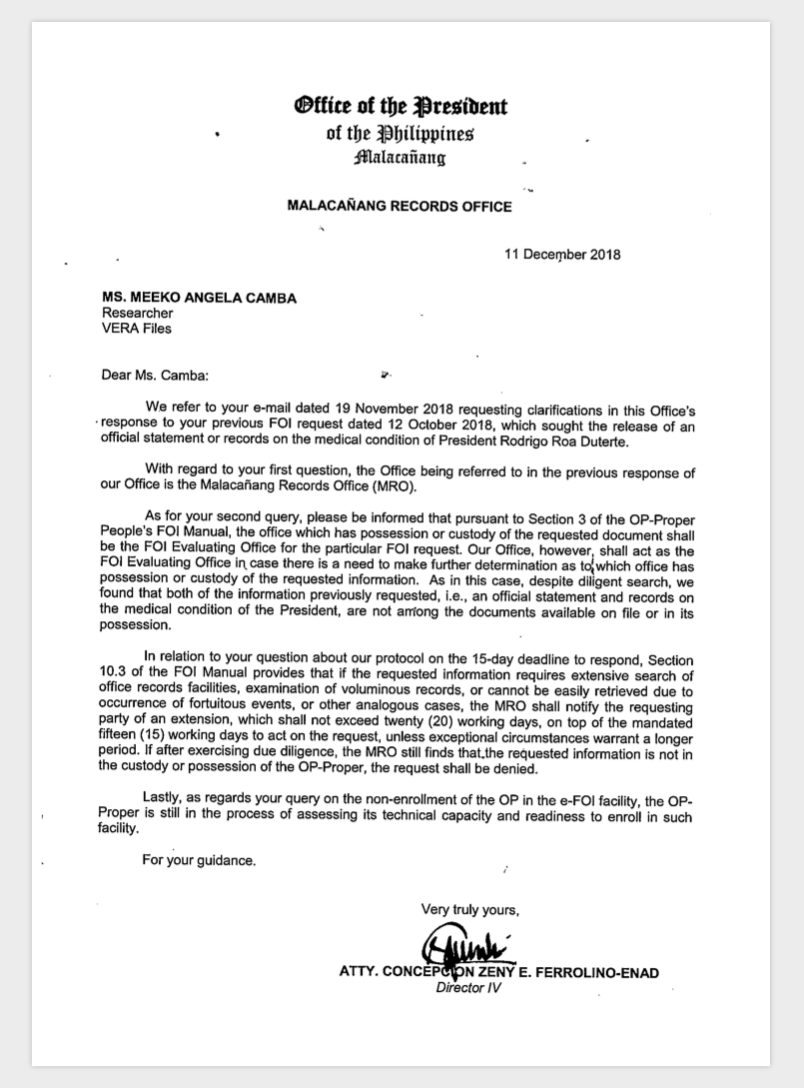

The MRO’s response to the second request came Dec. 11, a day after the 15-day deadline, and contained a letter from Enad. It said “there [was] a need to make further determination as to which office [had] possession or custody of the requested information.”

“As in this case, despite diligent search, we found that both of the information previously requested, i.e. an official statement and records on the medical condition of the President, are not among the documents available on file or in its possession,” the letter read.

The MRO’s response to VERA Files’ clarification on which department under the OP acted as the evaluating office of its initial request.

Duterte’s health saga

Rumors about the state of his health have hounded Duterte even before he was elected into the country’s highest office.

In February 2016, during the election campaign, he skipped a meeting with doctors and was brought to the Cardinal Santos Medical Center after he complained of severe migraine, reports said. But he refused to make public his medical records.

In his three years in office, there were a number of official functions that the president missed including while attending regional and international meetings like the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in Singapore in November 2018, and the Asia Pacific Economic Forum gala dinners for three years straight since 2016.

Here’s a timeline of the President’s publicized health-related issues:

Matter of national security

The 1987 Constitution frames the president’s health as a matter of national security.

Sec. 12, Art. 7 specifically states that–aside from public disclosure–the military chief and members of the Cabinet in charge of national security and foreign relations shall not be denied access to the president in case of serious illness.

When late ex-senator Blas Ople proposed this provision in the 1986 Constitutional Commission (ConCom), he said:

“The national survival can hang in the balance and therefore, the right of the people to know ought to be included in this Article on the Executive, not only the right of the people to urgent access to a President in a state of illness, but especially those who deal with the safety and survival of the nation.”

Fr. Joaquin Bernas, another ConCom member, in his comprehensive reviewer of the 1987 Charter said Sec. 12 “envisions not just illness which incapacitates but also a serious illness which can be a matter of national concern.”

As to who had the duty of releasing the information to the public, Bernas said, “it is understood that the Office of the President would be responsible for making the disclosure.”