NAVAL, Biliran – Bonifacio Jumetilco Sr. blames evil spirits for the motorcycle crash that could have killed him four years ago.

Rushing to catch a cockfight derby aboard a motorcycle that March afternoon in 2014, Bonifacio noticed how fast his son Joel was driving, so fast he said it felt “mura’g naglupad (like we were flying).”

Sensing his son might be drunk, Bonifacio told Joel to slow down, but to no avail; he recalls Joel responding, “Aw hawid lang, Tay, kay ako naghawid sa manobela (Just hold on tight, Pa, I’m the one driving).”

Minutes later, Bonifacio found himself crying for help, when the motorcycle lost control, and father and son got stuck in a ditch. Joel was unconscious, his face covered with blood. It took 30 minutes before help came.

“Kaingon gani ko og patay gyud (I thought he won’t survive),” said Bonifacio.

Bonifacio and Joel were not the only road users who crashed in this area here in Barangay Talustusan. They’re not alone in blaming the spirits, either.

Bonifacio narrating their experience

Talustusan barangay chair Arturo Saclolo, who estimates there have been around a hundred crashes and four deaths since this part of the road was concreted in 2005, also does.

“Gi-kuno kuno man pod niari nga damo og dakit dihang dapita (People say there used to be balete trees in the area), Saclolo says. Balete trees are believed to be dwelling places of supernatural beings.

Bonifacio’s wife Anacorita and his daughter Jocelyn are more cynical, and blame something more commonplace: drink-driving.

Indeed, Bonifacio’s story underscores a deeper problem, the inability of communities like Talustusan to implement road safety measures by regulating factors that increase the likelihood of crashes, among them drink-driving, speeding and unsafe road conditions.

Keeping residents from driving when drunk is already a challenge.

For one, the village due to budget constraints does not have the capacity to buy breathalyzers, which are necessary for enforcers in flagging down and confiscating the keys of drivers who have had too much to drink.

“Masuko man to kay unsa man imo kapasikaran nga naka-inom ko (They’ll get mad and would ask us how we know they’re drunk),” Saclolo said.

At the Biliran Provincial Hospital (BPH), identifying whether a person involved in a road crash is drunk is also a challenge, forcing officials to be creative.

“Inaamoy na lang talaga ng nurse on duty (The nurse on duty just sniffs the smell of alcohol),” said BPH director Joyce Caneja.

Last year, the BPH recorded 218 cases of road crashes, more than half the total involving motorcycles. This year, the hospital so far has recorded 73 crashes. There have been six deaths, all passengers onboard motorcycles.

Saclolo says most crashes happen in Talustusan’s during its fiesta celebration.

“Pero kasagaran dili pod taga ato (Most people involved are also not from the community),” Saclolo said

Naval Rescue Unit (NAVRU) head Raul Villordon has the same observation, saying the most number of road crashes they responded to since the rescue unit was formed in April 2017 happened during fiesta season in May.

“Kasagaran mga batan-on (Most of those involved are teenagers),” Villordon said.

From January to June this year, NAVRU has responded to 40 motorcycle crashes in the municipality of Naval alone. Nine of the cases happened in May.

Saclolo also thinks drink driving is not the sole reason for the road crashes in Talustusan, but the road condition as well.

“Kay og naka-inom lang taas man ang daganan ngano wala man nangatumba sa layo pa, diha man gyud mismo (We can’t blame drink driving alone. It’s a long road. Why didn’t the road crash happen somewhere in that stretch. Why only in that particular area)?” he muses.

The latest crash happened in August, and the victims are still recovering in a Tacloban hospital after undergoing surgeries.

Jocelyn notes that despite the persistence of crashes in the road stretch, the village council has done nothing to address the problem.

“Pagkahuman sa aksidente mura lang ug wala’y nahitabo (Every time a crash happens, they’ll just move on as if nothing happened),” she says, adding records are not even kept.

Portion of the 2.5-kilometer stretch of Barangay Talustusan road that claimed one person’s life in Dec. 2015. The driver according to residents was speeding while under the influence of alcohol.

No road signs can be found in the entire stretch of the barangay road. Saclolo said the barangay council once put a warning sign written on a cardboard in the area where Bonifacio and Joel crashed, but it was eventually destroyed by rain.

Local governments under the Motor Vehicles User’s Charge (MVUC) law may request for funds for road maintenance. Yet, the Department of Interior and Local Government’s guideline on special local road fund, however, gives village roads the least priority for funding.

Asked whether he has approached the Naval LGU for help to improve the road condition and installation of road signs in Talustusan, Saclolo said, he only waits until the municipal government announce availability of funding related to road safety which he can avail of.

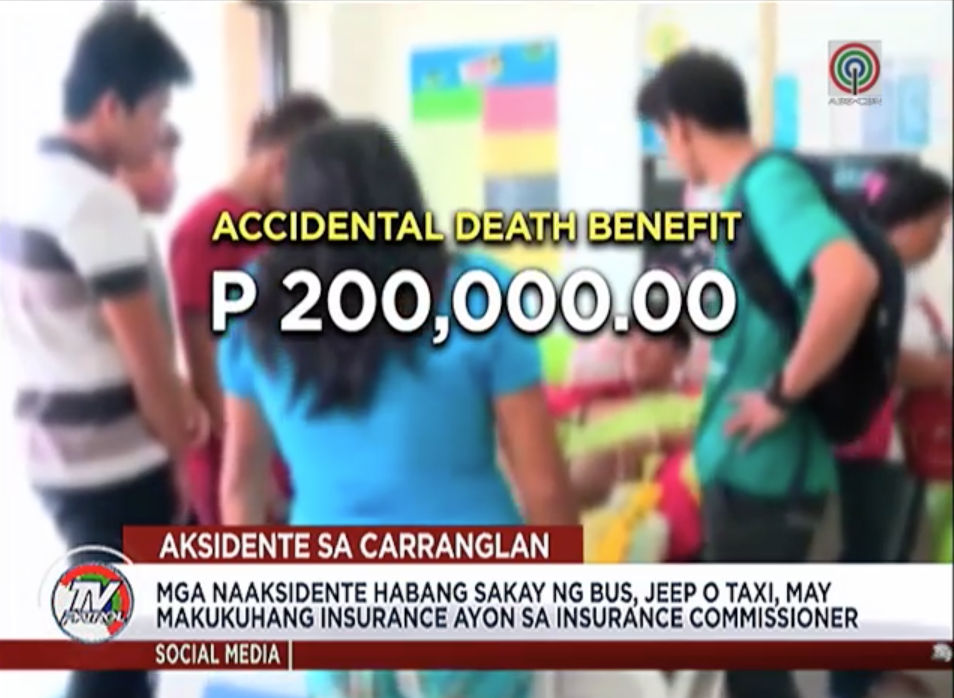

The Jumetilco family spent over P200,000 for Joel’s reconstructive surgery, purchasing a titanium plate to fix his broken jaw. Follow-up checks also cost them money.

Bonifacio only sustained minor bruises and experienced back pain for several weeks.

To this day, whenever they pass by the area where the crash happened, he still cannot help but remind his kids to slow down, and for good measure, honk to drive the evil spirit away.

This story is produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.